In October 2017, we carried a story Fraud committed using ministry letterhead [link] about how a worker was misled about the salary he would be getting before he signed on for a job in Singapore. While, as we explained in that article, we did not know who exactly was the culprit, the fact that a scam was afoot could be seen from the two In-Principle Approvals (IPA) for this job. TWC2’s understanding is that only one authorised IPA should exist. Why were there two different ones with different salaries? We argued that it was quite apparent that one of them was fraudulent.

In that instance, MOM’s response was to turn defensive, declaring that there was “No information to suggest that there was fraud” despite the two different IPAs in front of their very eyes which contradicts their insistence that they only issued one IPA. You can see their wholly inadequate response here [Link]. It comes with our rejoinder pointing out how their response still fails to deal with key questions.

| As an aside:

An alternative possibility is that our understanding is incorrect: that MOM’s processes do indeed allow two or more equally valid IPAs with different details to co-exist. If so, it’s a recipe for utter confusion. MOM cannot have it both ways. Either it’s a one-authentic-IPA system in which the existence of a different version of an IPA is prima facie evidence of fraud or it’s a multi-authentic-IPA system in which MOM’s own system has a fundamental weakness. Interestingly, MOM has not explicitly said which way it is. |

On the assumption that it is a one-authentic-IPA system, we now highlight three more highly suspicious cases.

Before moving on however, some readers may need an explanation as to what an IPA is and its significance.

![]()

The In-principle Approval (IPA)

When an employer has identified someone in a foreign country as a worker he’d like to employ, the employer (or local employment agency acting on his behalf) goes online to submit an application for a work permit. The online form requires quite a fair bit of biodata and passport information, but what is material to this discussion is that the online form requires the employer (or his agent) to input:

- Basic monthly salary

- Monthly deductions for housing amenities and services

- Monthly deduction, others

- Fixed monthly allowances

- Fixed monthly salary

- Monthly salary after taking into account fixed monthly allowances and deductions

Approvals (or rejections) come rather quickly — a matter of days. If the application is approved “in-principle”, two differently-formatted versions of the “In-principle Approval for Work Permit” (IPA) can be printed out by the employer. One is the employer’s copy, which also states his monthly foreign worker levy; the other is the employee’s copy. Although differently formatted, the details should be the same. The employer (or his agent) is responsible for forwarding the employee’s copy to the worker, who at this point in time, is still in his home country.

The intention — and it’s a worthy one — is obvious. It is to ensure that the worker is informed of the job details before he takes on the job and comes to Singapore.

What TWC2 is very concerned about is the transit of the employee’s copy via the employer. Being only electronic documents, they are easily photoshopped. This vulnerability does not seem to have alarmed MOM to action.

![]()

Falcon500

Of the three suspicious cases, the iffiest case is that of a worker we’ll call “Falcon500”. It is an iffy case mainly because he lacks copies of the papers he says he saw. Nonetheless, without any prompting, he tells a story that is entirely plausible given what we have heard from a few other workers, and with details that he would not have known if he had not experienced it himself. Thus, there is a fair degree of credibility despite his lack of paper evidence.

Falcon500 received an IPA while he was in Bangladesh but he says he now cannot remember what the basic salary stated on the IPA was. As a first-time worker, he didn’t know the importance of documents in a paper-based culture like Singapore’s. Instead he relied on verbal promises — details of which are irrelevant to this story about fraudulent documents.

Very soon after arrival in Singapore, Falcon500 was taken to MOM by the company driver to get his Work Permit done. As he was alighting from the lorry, the driver gave him a stack of papers. Falcon500 did not look closely at the papers. He went into MOM unaccompanied and was processed routinely, except that an officer then came up to him and passed him a piece of paper. According to Falcon500, the officer explained to him what the piece of paper said: That his salary was $1,600 per month and that if the employer didn’t pay him that, he could lodge a complaint at MOM. Falcon500 had a brief glance at the paper before leaving MOM and remembered seeing the number “1600” written on it. He thought he could re-read the piece of paper at leisure after he got back to the dorm.

(Why is this significant? What Falcon 500 describes is a “salary reduction notification” — a new form recently developed by MOM. Because it’s new and does not affect the vast majority of foreign workers, it’s very rare for workers to know about this form unless they’ve received one themselves.)

Alas, when Falcon500 returned to the lorry in the car park, the driver took away all his papers despite his protests.

About five months later, Falcon500 lodged a salary complaint. Somewhere along the mediation process, he said he was given (not clear by whom) a copy of the IPA that looked like this, stating a basic monthly salary of $500.

Falcon does not consider it a binding IPA.

| As an aside:

As a further wrinkle, the mediation officer also insisted that his deductions were not $100 + $50 as stated in the above IPA, but $100 + $100. The officer apparently relied on figures stored in MOM’s computer as at 26 June 2018. Firstly it is not clear what the source of those computer details are — did Falcon500 ever agree in writing to an increase in deductions? — and secondly, what his salary was on 26 June 2018 (dubious provenance of those details aside) is irrelevant, since the key question should be: What were the contract terms at start of employment? It is of concern that at MOM and TADM, such fundamental and logical distinctions are not made. However, it is not necessary to get into the details of the case. The above paragraph is merely to show readers how absurdly complicated cases can get, and how distant MOM’s processes are from the method as laid down in a recent High Court judgement — which will be explained at the end of the article. |

Our point is this: On thumbprinting day, an MOM officer had told the worker his salary should be $1,600. The officer also said it in a way to indicate to Falcon500 that the employer was attempting to lower the salary improperly.

Where would that MOM officer have gotten that $1,600 figure from if not the original IPA? Thus, there is a strong hint that there was another IPA.

But if so, why is there now an IPA that states basic salary to be $500? Is one of them fake?

![]()

Toucan000

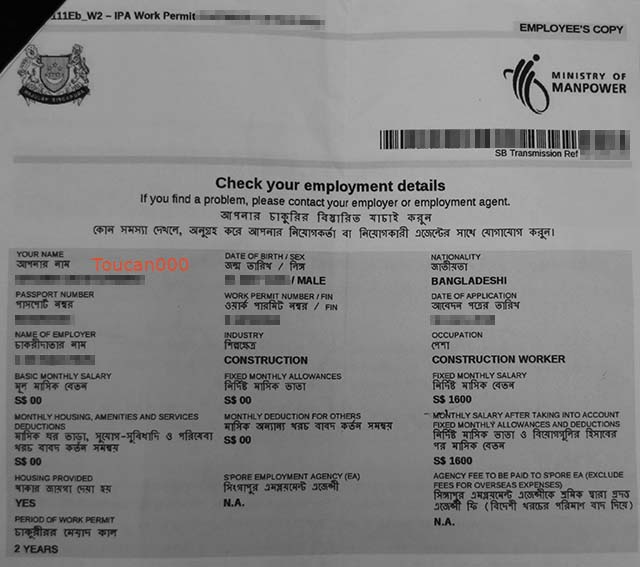

A worker we shall refer to as “Toucan000” received an IPA while he was in Bangladesh that was like this:

The most striking thing about this IPA is that the basic salary is stated as zero. It’s not clear why Toucan000 accepted such an IPA, though he was reassured when he noted that the fixed monthly salary would be $1,600 a month. The average Bangladeshi worker would not be able to distinguish the nuanced differences between a basic salary and a fixed monthly salary.

Months later, when he lodged a salary complaint, MOM told him that the details in their computer do not match what was on the IPA he had in hand. Instead, the computer records show

- Basic salary = $468;

- Fixed Monthly Deductions = $1132;

- Deductions for Housing and Amenities = $400;

- Other Deductions = $200;

Note: TWC2 had emailed MOM for these details, but MOM didn’t reply to TWC2. Instead, they gave these numbers verbally to the worker who may have remembered them slightly inaccurately. Why doesn’t MOM provide formal, detailed replies in writing? Secondly, are those details provided by MOM to the worker details of the original IPA? Or details as at a certain later date. and if so, who entered those details?

Nonetheless, we don’t need to resolve the many layers of Toucan000’s case to see the elephant question in the room: So where did the above-pictured IPA with zero basic salary come from? Who manufactured it? Does MOM accept and approve work permit applications where basic salary is nil? Or was it done by an intermediary photoshopping the original IPA before sending it to the prospective worker in Bangladesh?

Pelican600

Pelican600 received an IPA while he was in Bangladesh that was like this:

The most striking thing is that the numbers don’t add up properly. Basic salary ($600) + fixed allowances ($0) – housing deductions ($350) – other deductions ($250) produce a net fixed monthly salary of zero, not $1000 as stated above.

TWC2 social workers also noticed that the blank space between “S$” and “600” in the “basic salary” field was too wide. Likewise in the “fixed monthly salary” field. The thought that immediately comes to mind is that there was initially a figure of “1600” in the basic salary field, but the digit “1” was manually erased.

When Pelican600 raised a salary claim, he told us that the mediation officers just took a pen and added a “1” in the “basic salary” field, as if it was just an unintentional printing or typographical error at the start.

Was it really?

![]()

Four crime scenes

Taken together with the case written about last year, we now have four “crime scenes”. All the three cases we describe above are (as of time of writing) going through tortuous processes. Yet, in Liu Huaixi v Haniffa Pte Ltd [2017] SGHC 270, the judge had laid down a simple rule of thumb, which if followed, would simplify dispute resolution processes.

In paragraph 31 Justice Lee Seiu Kin laid down the default position:

Given the statutory intent of the IPA, the court would take as factual an employer’s declaration of the basic monthly salary in the IPA because he must be presumed to be truthful when he made the declaration.

And in paragraph 33, he elaborated,

Indeed, I would go so far as to state that even if there was a written contract of employment which provides for a monthly basic salary of less than the sum stated in the IPA, the burden would lie on the employer to show why the IPA figure does not reflect the true salary. For example, the employer may adduce evidence to prove that the sum stated in the IPA is different from the amount declared by him in the application for the work permit and somehow an error had been made in the IPA by MOM. Or the employer can admit that he had made a false declaration in the work permit application, thereby attracting other consequences for himself. I do not intend to limit the possibilities save that they probably lie somewhere between these two extremes. Given the statutory framework of the IPA, the amount stated in it would constitute prima facie evidence of the basic monthly salary of the employee.

In each of the above-mentioned cases, workers asked MOM for a reprint of the original IPA that was issued in order to apply the dispute resolution method as indicated by the above judgement. In each case, MOM refused, no reason given.

Why is MOM taking such a ridiculous stand that flouts the law’s intent?