Nazmul (left) and TWC2 volunteer Sraboni (right) who helped translate, joyful after his Tribunal victory

When we took on Nazmul’s salary claim, it looked like it would be one of the most uphill cases we’ve ever helped with. He had virtually no documentation about payments; he was unfortunate in not having much schooling, unable to speak English; and the claim calculations prepared for him by officials at TADM were inaccurate. TADM stands for Tripartite Alliance for Dispute Management, the unit in the Ministry of Manpower that handles the first stage of salary claims.

When he finally prevailed at the Employment Claims Tribunal (the second stage of the claims process) with a judgement in his favour, it was a supremely affirming moment for our volunteers and staff who had put in months of work to help him. Naturally, for Nazmul, it was the sweetest of victories too.

Consider this: Without much education, he had to represent himself in court-like proceedings conducted in English. He had little direct evidence to support his case. It would be daunting even for a university graduate in any subject other than law.

This is a long article. It will go into considerable detail about the background and the evidence in this case. We hope it is interesting and informative precisely because it goes into sufficient detail.

Background

Nazmul Md received an In-principle-Approval (IPA) from the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) in November 2022 for a Training Employment Pass. The IPA, whose details would have been based on declarations made by the prospective employer, stated that his occupation would be as a cook, and his salary would be in two parts: $2,800 in Basic Monthly Salary + $200 in Fixed Monthly Allowance. This meant that he was entitled to a fixed monthly salary of $3,000 (hereafter, the “salary”), before overtime pay. In submitting an application for an IPA, the employer, Obayed Holdings Pte Ltd, would have declared that the salary details were a truthful reflection of the (verbal) contract that had been made with Nazmul.

He was entitled to overtime pay (if he worked overtime hours) since, as a cook working with his hands, he would be classed as a manual labourer, and under the Employment Act, any manual worker with a salary under $4,500 should be paid an overtime rate for extra hours.

The approved period of employment was three months – the normal duration of training passes.

Nazmul arrived in Singapore on 13 January 2023 and began work the following day. He was assigned to be the cook at a canteen stall in a migrant workers’ dormitory in Punggol. He would discover that he was largely working alone (see pink box). Obayed Holdings’ Bangladeshi food stall was one of only three food stalls in a dorm with 13,000 residents, but since the majority of migrant workers in Singapore relied on deliveries of catered meals, it should not be assumed that Nazmul had to cook for thousands of workers. Nonetheless, he was busy.

His workday began at 11:30pm, working through the night to 5:30am the next day. It then restarted at 11:00am and continued to 5:30pm. He had no meal breaks, consuming his own meals outside those hours. In total, he worked twelve and a half hours each day, seven days a week, including Sundays and public holidays. He did everything from cutting vegetables, to cooking to washing dishes.

A Training Employment Pass is meant to enable companies with international operations or international affiliates, to bring in someone from abroad in order to provide training or an apprenticeship while here. That is why it is limited to three months. It implies that the foreigner should not be working alone, but under the close supervision of a trainer.

TWC2 has seen many instances where small companies with no work permit quotas abuse this category of training passes to hire workers from abroad and use them as cheap labour.

A Training Employment Pass also implies that the trainee should be paid a salary roughly commensurate with regular Employment Pass holders. But if the intention is to have cheap labour, then this immediately sets up a contradiction.

What Nazmul didn’t know at the time, being new to Singapore, was that he was not supposed to start work until MOM had issued him his Training Employment Pass. The normal process would be for the employer to inform MOM that the worker had arrived in Singapore and to request that a pass be issued to the new employee.

Obayed Holdings did not register for the work pass until 28 February 2023, which meant that Nazmul was put in jeopardy – open to accusations of working illegally – for the six weeks between 14 January and 1 March 2023.

Why did the employer delay? Obviously we cannot read the employer’s mind, but a very likely motive lies in his need to have Nazmul working for him for as long as possible. The IPA clearly stated three months as the permitted duration of employment. By exploiting Nazmul’s ignorance and making him work six weeks before the issuance of the work pass, the employer might be intending to have him for a total of four and a half months instead of three.

This delay by the employer would have major consequences for Nazmul. When the latter went to TADM to lodge a complaint, he was informed at TADM that he could only legally work in Singapore after the work pass card registration application had been made. Everyone concerned, including TWC2’s case officers, then felt that it might be wiser not to press a claim for unpaid salary for the first six weeks because doing so might open a Pandora’s box of legality. However, waiving that part of the claim meant that Nazmul would suffer the loss of salary – he was not paid, of course! – for those six weeks, through no fault of his own.

Non-payment of salary

Unfortunate as it is, for the rest of this story, we will set aside the question of salary for the first six weeks.

The only payment he received were two cash payments of $1,200 each. One payment was made in April, purportedly being his salary for March, and the other was made in May, purportedly being his salary for April.

Things didn’t look good; there were bad omens. In the first week of April, Nazmul was asked by Atikur Rahman, the younger brother of Obaidur Rahman, whom he knew as the company boss, to sign three blank pay slips. No employee should ever be asked to sign blank pay slips; the very request is a red flag. We later found from official filings that Obaidur, a Bangladeshi national, held 50 percent of the shares in the company, with the rest held by a Singaporean, Chew Lai Yee, who was likely the silent partner.

This request was repeated in May. On the afternoon of 3 May 2023, Nazmul said in his later filing to the Employment Claims Tribunal, he was asked again to sign another three blank pay slips. This time, he added a date to the three blank payslips “3/3/2023”, which was a mistake since the intention was to write “3/5/2023”. He also took photos of the three blank payslips. They only had his signature and (the wrong) date, but nothing else was written into them, as can be seen from the photos later presented as evidence in the Tribunal.

Nazmul’s photo of one of the blank payslips he was made to sign on 3 May 2023.

The erroneous date and photos, which came with date stamps, would have major consequences down the line.

Not having been properly paid ever since the beginning, Nazmul stopped working for Obayed Holdings on the 18th or 19th of May. He then went to make a complaint at MOM and TADM.

A day later, on Tuesday, 23 May 2023, he met with the boss Obaidur Rahman in the company’s offices. Nazmul had his mobile phone on and recorded about 35 minutes of the conversation (in Bengali). As part of his evidence later submitted at the Tribunal hearing, there was a certified translation and transcript of a key part of the conversation right after he insisted he was quitting.

Nazmul: I will go away, I will not stay.

Obaidur: You stay as long as you can, and settle down here.

Nazmul: No I do not need. I don’t need to work in such company which can has their employees to sign on a blank paper.

Obaidur: Did this company asked you to do this job? Before joining this job, before doing it, did you understand clearly anything from the company?

What is notable is that Nazmul clearly states that he was being made to sign blank pieces of paper. Instead of refuting this, Obaidur, in his next sentence, changes the subject.

At TADM

One troubling thread running through this story concerns the quality standards at TADM when they handle salary disputes. However, in order to explain what troubles us, we need to first outline what TADM’s role is, and how anything short of the utmost attention to detail in their performance of that role can seriously damage a worker’s case at the Tribunal. Falling short of standards can therefore undermine a claimant’s right to justice, a fundamental tenet of international conventions and Singapore’s own constitution.

It’s not just a question of individual TADM officers and their job performance. Concerns also centre on the design of process – a systemic issue and the responsibility of policy makers.

The inherent contradiction is this: TADM is both mediator and gatekeeper. As mediator, they may adopt the stance that they should not be the party to determine how much a worker should claim when he feels he has been wronged. They may let a worker decide for himself what he wants to claim for, albeit guiding him as to what would be legitimate grounds or limits, based on law. If a worker omits to claim for something because he is not even aware he is entitled to that, is it TADM’s responsibility to inform him? At TWC2, when we work with worker-clients, we think it’s only professionally conscientious that we should point it out.

We consider it only reasonable to take into account the fact that most migrant workers cannot be expected to know all the details of labour law, and know exactly what they’re entitled to and what they’re not. We will take the trouble to go through each and every entitlement to make sure that a worker is not unaware of something that is crucial.

Nazmul came to TWC2 for the first time on 26 May 2023, a few days after he first went to MOM and TADM. By then, he already had in hand a printout from TADM stating the elements (and quanta) of his claim. In other words, TADM had fixed his claim amounts to be mediated in the coming days and weeks. The problem was that TADM’s calculations were wrong.

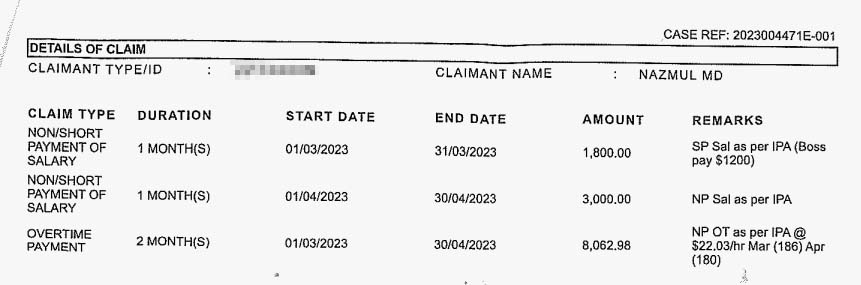

Nazmul’s claim calculations as at 26 May 2023, as initially prepared by TADM. Claim amounts for the month of May would be added later.

How could that happen? Nazmul probably spoke to TADM about the fact that he worked lots of “overtime”, and must have given details about his working days and working hours. What he would not have known is that in law, not all extra hours are “overtime”. There is also the concept of rest day pay (Sundays) and public holiday pay, distinct from overtime pay. When salary claims are computed, these must be separately accounted for. Did TADM officers not tease apart the numbers?

The mistakes

A bit more detail here might make the rest of this story easier to understand.

Firstly, Nazmul worked seven days a week. That meant he worked Sundays and public holidays. The Employment Act makes a provision for payment for work done on rest days (Section 37) separate from the provision for work done overtime (Section 38). These two provisions provide for different rates of payment. Working on a Sunday at the employer’s request – which was so in Nazmul’s case – entitles him to twice his basic rate of pay, whereas working overtime (i.e. beyond 44 hours a week) entitles him to 1.5 times the basic rate of pay.

Nazmul’s claim, as formalised by TADM, should therefore have had a line item for Sundays and another for public holidays. It did not. Instead, TADM treated all his work hours in excess of his normal hours as overtime (at the 1.5x rate). This understated his entitlement.

To make things worse, as far as TWC2 knows, there is no formal and easily available process, carefully explained to workers, for correcting TADM’s mistakes. His claiming rights were thus limited by the erroneous numbers on the printout.

There was another mistake on the calculation printout. Nazmul received two cash payments of $1,200 each. The first was in April, purportedly his salary for March. The second was in May, purportedly his salary for April. Somehow, TADM only recorded his first cash payment. In so doing, whilst TADM correctly adjusted the claim amount for his fixed monthly salary for March ($3,000) down by $1,200 to a nett $1,800, it did not make a similar adjustment for April. Instead, the initial calculation and later on, the Claim Referral Certificate (explained in the blue box) generated by TADM stated a claim amount for the full April salary of $3,000. This was an overestimate of Nazmul’s rightful quantum.

A Claim Referral Certificate is a document generated by TADM after mediation has failed to produce a settlement between parties, referring the dispute to the Employment Claims Tribunal. The Tribunal will not consider claims outside what is listed in the Certificate. Therefore, errors in the Certificate are significant, and in a sense, limiting. That’s why it is so important that TADM cannot afford to be careless.

Overestimating is not a “good thing”. It can still jeopardise a worker’s case at the Tribunal. If the employer can prove that the over-estimated amount is false, it can damage the credibility of the worker, and that damaged credibility can cascade onto other line items.

TADM organised mediation sessions between parties. These were conducted online, supplemented by additional exchanges via WhatsApp.

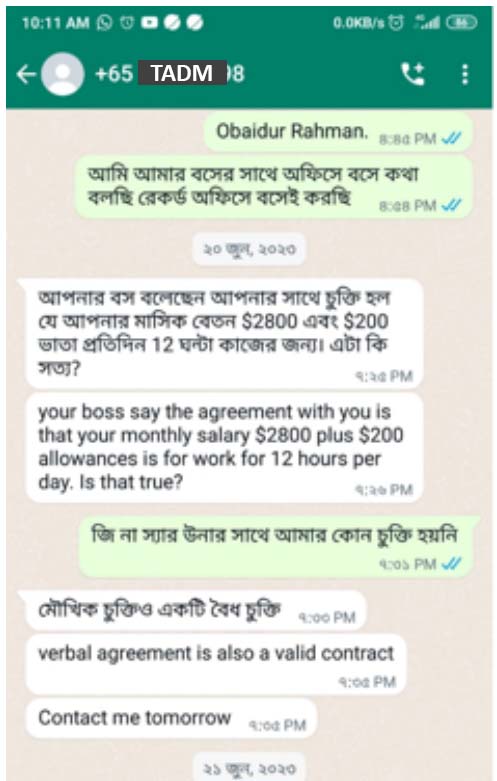

One of those exchanges also raised red flags about standards at TADM. Apparently, the employer had countered that Nazmul should not be claiming for overtime pay because he had agreed to work twelve hours a day. TADM then asked Nazmul if this was true. Here’s what we saw on Nazmul’s phone:

WhatsApp messages exchanged between TADM (white) and Nazmul (green) in June 2023.

The shocking thing about this exchange was that the TADM mediator was suggesting to Nazmul that a verbal agreement to work 12 hours a day for no overtime pay was valid and enforceable. No, it is not. It is trite law that any purported private contract in violation of statutory law cannot be valid. The Employment Act is abundantly clear that hours in excess of 44 per week (let alone Sundays and public holidays) have to be paid at least the minimum overtime rate of 1.5 times the basic rate of pay.

Anybody seeing such a message from TADM would ask whether the officers there even know the Employment Act or basic tenets of law. Do TADM officers feel a responsibility to conform with the Act’s provisions when conducting themselves? This is serious, because one cannot expect migrant workers to be familiar with statutory law and be able to rebut such insidious remarks forcefully. On the contrary: workers may be misled to think their salary claims are on weak ground and may feel pressured to withdraw their claims.

Instead, the TADM officer should have told the employer straight off that such an argument would be untenable. It’s fair enough that the TADM officer should relay the employer’s (empty) argument to Nazmul for his information, but it is improper to add the subsequent remark implying that the employer had a valid point.

Ultimately, no settlement was reached at mediation. TADM then issued a Claim Referral Certificate, escalating the matter to the Employment Claims Tribunal (ECT). The errors made in the initial printout of amounts owed were largely carried over to the Referral Certificate, and from this point on, the scope of the adjudication to come would be confined to the line items and the numbers in the Certificate. TADM’s gatekeeper role meant that its sloppiness had the effect of limiting the justice to be delivered by the Tribunal.

Nazmul’s Claim Referral Certificate dated 11 July 2023.

As can be seen from the image above, the amount involved was $16,729.48, but because of computational errors, this amount does not fit the evidence fully.

At the Tribunal

The Tribunal hearing took place on 8 November 2023. It was held online and Nazmul had to appear via videolink. If not for TWC2, he would have had no idea how to set up a video link; this too is another issue about digitisation and access to justice.

There were two interesting elements to the employer’s defence. One was with respect to Nazmul’s claim for basic pay and the other was about his overtime pay. TADM having omitted a line item for Sundays and public holidays in the Claim Referral Certificate, this angle could not be pursued in the hearing.

Basic pay

Nazmul argued that he was owed $1,800 in unpaid basic pay for March and another $1,800 in unpaid basic pay for April. Notice here that Nazmul did not proceed with a claim for $3,000 for April even though TADM calculated, and wrote into the Claim Referral Certificate, a quantum of $3,000 for that month – because, as mentioned above, TADM did not take into account that Nazmul had received $1,200 in cash for April. Nazmul only pressed his claim for the lower amount of $1,800 for April. TWC2 had counselled Nazmul to be scrupulously honest in his arguments before the Tribunal.

As for the partial month of May, there was a weird amount of $2,192.22 that TADM had calculated as Nazmul’s owed (pro-rated) salary before overtime pay. This figure was entered into the appendix of Claim Referral Certificate. Again, being scrupulously correct, Nazmul only pressed for $1,920, a figure he could support with proper calculations.

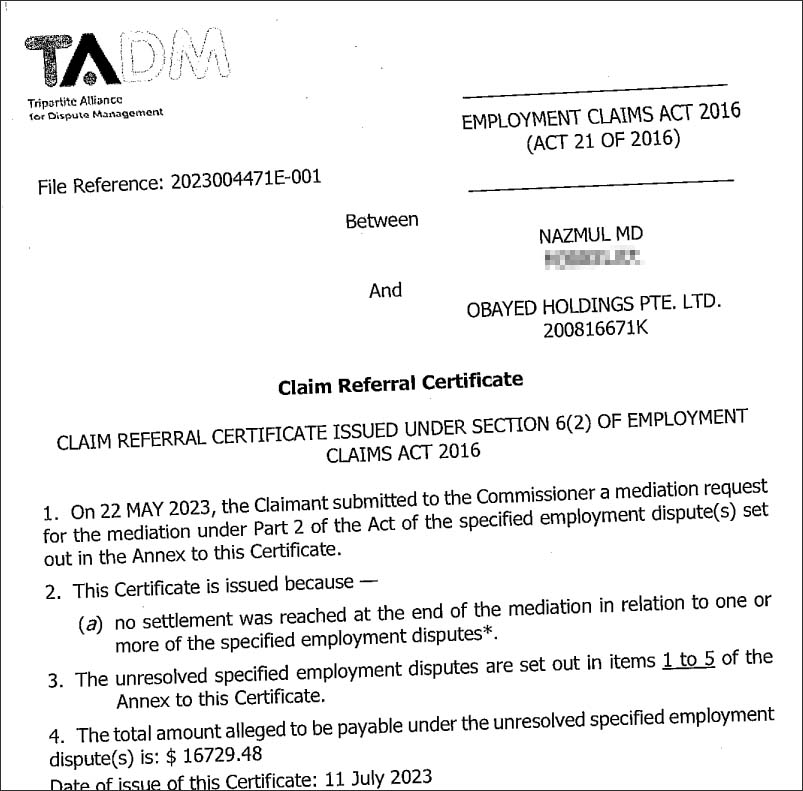

With respect to the salary for March, the employer submitted into evidence a cash advance voucher, dated 3 March 2023, attempting to show that Nazmul had taken a loan of $2,500. A cash advance, if genuine, can be offset against owed salary. But was it genuine?

Nazmul argued that it was not, and that this “signed” voucher had been falsified. The signature on that supposed loan voucher was identical to the blank voucher he was made to sign on 3 May 2023 (proven by the time stamp on the photograph), and which he had mistakenly dated “3/3/2023”. How could it have been written up in March and then suddenly blank two months later in May?

The fake loan voucher, compared against the blank voucher Nazmul signed in May.

The employer tried the same trick regarding the salary owed for April. Obayed Holdings tendered a voucher that purported to show that Nazmul had been paid $3,000. In response, Nazmul said to the Tribunal, “The signature comes from one of 3 blank payslips that I signed in April 2023.”

By effectively showing these vouchers to be false, we believe Nazmul successfully impeached the credibility of the employer.

Overtime pay

Regarding overtime pay, the employer admitted that they had not paid overtime wages to Nazmul, but this was because, as they argued, Nazmul did not perform overtime work. In support of such a claim, they submitted time cards that seemingly showed Nazmul to have worked merely 44 hours a week or even less. The time cards claimed that on weekdays, he worked four hours from midnight to 4 am and noon to 4 pm. On Saturdays, just noon to 4 pm.

Nazmul had never seen these so-called time cards before. He had reason to be suspicious. In any case, the times stated there were wildly inconsistent with the hours he worked.

At the Tribunal, Nazmul pointed out that the stall was open seven days a week, with Sundays and holidays the busiest days, and he was the only cook. There was no one else. The employer’s argument that he was not on duty for those other hours was simply not credible.

Moreover, if Nazmul had indeed worked just 44 hours a week or less, why did the employer advance the argument (see the imaged WhatsApp exchange above) that no overtime pay was owed becase there was a contractual agreement that Nazmul work 12 hours a day? There would have been no need to advance such an argument.

The Tribunal’s decision

After a hearing lasting most of an afternoon, a decision was handed down around 5:30pm. The employer was ordered to pay Nazmul the following owed amounts:

Salary for March 2023: $1,800.00

Salary for April 2023: $1,800.00

Salary for the partial month of May 2023: $1,750.00

Overtime pay for March and April: $6,653.06

Overtime pay for May 2023: $1,674.28

Total: $13,677.34

Though the ordered amount was about three thousand dollars lower than the total in the Claim Referral Certificate ($16, 729.48) Nazmul actually got nearly all that he was asking for. That was because the Claim Referral Certificate from TADM badly overstated his overtime and his outstanding salary for April.

And yet, happy though Nazmul was, the outcome cannot be said to be truly fair to him. TADM had completely omitted a line item for Sunday and public holiday pay, and once it was omitted, it was outside the jurisdiction of the Tribunal to consider it. Secondly, Nazmul was also a victim of the employer’s delay (we believe, deliberate) in registering him for his Training Employment Pass. The six weeks that elapsed and in which he was working without a work pass, put him on very uncertain ground when it came to claiming for his salary for that period. Those six weeks would have been worth about $8,000 in basic and overtime pay.

Do undocumented workers enjoy the protection of labour law?

The question of whether someone who was working without a government-issued work pass has salary rights merits a bit of discussion. It is not at all obvious that he does not have salary rights, although in asserting his rights, he may open himself to criminal prosecution for working without a work pass.

There is a similar case from Ireland (see Irish Times article “Court upholds chef’s award of €91,000” dated 26 June 2015) wherein a Pakistani cook, Muhammad Younis, worked seven days a week and up to 77 hours each week, for very little money. He was also working illegally after the employer failed to renew his work permit. Nonetheless, when he brought a claim to the authorities, the rights commissioner awarded him 91,134€. When the employer (Younis’ cousin Hussein) failed to pay up, the matter went to the Labour Court which formally ordered Hussein to pay. Ultimately, the matter went all the way up to the Supreme Court, essentially over a technicality, but the bottom line was that Younis won the appeal.

Singapore’s Employment Act defines an employee as “a person who has entered into or works under a contract of service with an employer”, with some exceptions relating to certain classes of government officials, seafarers and domestic workers. It says nothing about work passes, and therefore having or not having such a pass does not appear to be material to the protections the law provides, so long as there subsists a contract of service.

This page may also be useful reading – about labour rights for undocumented foreigners in the European Union. Here’s a key sentence within: “the [EU] directive explicitly reiterates that undocumented workers have a right to be paid their wages, at least at the level of the statutory minimum wage or as agreed in collective bargaining agreements.”