Water too is fungible

Employers who hire migrant workers on Work Permits have to pay a Monthly Foreign Worker Levy. The amount varies from the low hundreds of dollars to nearly $1,000 per month depending on the industry sector, the worker’s skill level and other factors.

It is illegal for employers to make workers pay the levy; this is clearly written into law and publicised on the Ministry of Manpower’s website https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/salary/salary-deductions#deducting-salaries-of-foreign-workers where it says:

Your employer is not allowed to make deductions to your salaries under any circumstances, for the following purposes as specified in the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act:

- As a condition for employing or continuing to employ you.

- For costs related to your employment:

– Work pass renewal

– Security bond

– Medical insurance

– Repatriation costs

– Compulsory training

– Medical fees

– Levy payment

Yet, the Employment Act allows employers to make deductions from employees’ salaries for “other” purposes so long as employees have agreed to such deductions. Section 27(1) of the Act says “The following deductions may be made from the salary of an employee:” and goes on to list eleven authorised deductions, of which item (i) says “any deduction (other than a deduction mentioned in paragraphs (a) to (h), (j) and (k)) made with the employee’s written consent“.

Employers of migrant workers are known to use this “any deduction” or “other deduction” as a kind of blank cheque to claw back a part of their salaries for unspecified purposes. Since money is fungible, it is easily leveraged to get money back from the worker in order to pay for the levy, especially as the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) does not seem to conduct any routine checks.

Strictly speaking, employers cannot do that because the general principle is that any deduction made to salaries should correspond to the real value of goods or services supplied to benefit employees (with employees’ agreement), but the absence of regulatory checks renders the principle abstract.

It’s worth noting that the same Employment Act also envisages a situation where an employee no longer wants to receive such goods or services from his employer, in which case, the employee can withdraw consent for the corresponding deduction. Sections 27(1A) and (1B) say:

(1A) An employee’s written consent for any deduction mentioned in subsection (1)(d), (e), (i) or (j) may be withdrawn by the employee giving written notice of the withdrawal to the employer at any time before the deduction is made.

(1B) An employee cannot be penalised for withdrawing a written consent for any deduction mentioned in subsection (1)(d), (e), (i) or (j).

However, in practical terms, Sections 27(1A) and (1B) are meaningless for migrant workers, as we shall discuss further down. But first, we have a real example of a worker’s salary terms to unpack.

Billal’s In-Principle Approval

When an employer wishes to hire a foreigner on a Work Permit, the employer (or his Singapore-licensed agent) makes an online application at MOM. The employer has to furnish information about the salary terms as well. Upon approval, MOM issues an In-Principle Approval for a Work Permit (IPA), a PDF document is issued in which the salary details are spelled out.

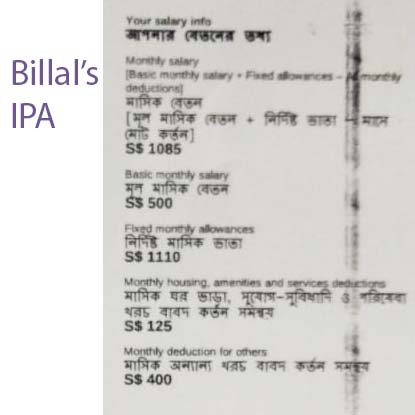

Billal (name changed) received his IPA in March 2025 and started on the job soon after. Three months later, he came to TWC2 for assistance over incomplete salary payments and related issues. We naturally asked to review his employment documentation and that’s how we noticed what we call “numerical gymnastics” on his IPA. The relevant portion of his IPA is shown below.

For clarity, this is how Billal’s salary was structured:

| Salary element | S$ (monthly) |

|---|---|

| Basic salary | 500 |

| Fixed allowance | 1,110 |

| GROSS fixed salary | 1,610 |

| Deduction for housing, etc | 125 |

| Deduction for other | 400 |

| NET of deductions | 1,085 |

It struck us as unnecessarily complicated. The large amount for fixed allowance – $1,110, which is more than twice his basic salary – and the deduction for unspecified Other ($400) flashed at our eyes. They indicate that this salary was structured with secondary motives in mind. What these might be, we shall discuss below.

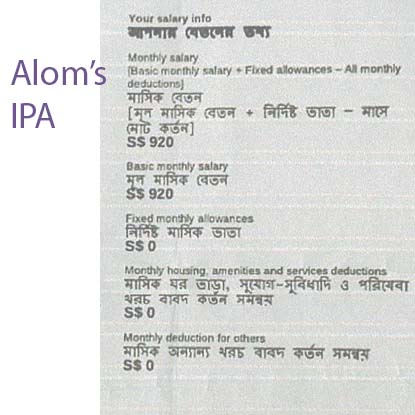

For comparison, here is the relevant part of another worker’s IPA. This other worker – we’ll call him Alom – has a nett salary in the same ballpark as Billal’s, yet his IPA does not have the embellishments that Billal’s IPA has. It is this contrast that makes Billal’s IPA noteworthy.

| Salary element | S$ (monthly) |

|---|---|

| Basic salary | 920 |

| Fixed allowance | 0 |

| GROSS fixed salary | 920 |

| Deduction for housing, etc | 0 |

| Deduction for other | 0 |

| NET of deductions | 920 |

R1 grade construction worker and levy cost

With respect to the Monthly Foreign Worker Levy, construction workers from “non-traditional source countries” such as Bangladesh, are classified into two Work Permit tiers: “basic skilled” and “higher skilled”. For basic-skilled workers, the levy is $900 a month. For higher-skilled, it is $500.

That linked page also says that “At least 10% of your construction Work Permit holders must be Higher-Skilled (R1) before you can hire any new Basic-Skilled (R2) construction workers or renew the Work Permits of existing R2 construction workers. Work Permits of any excess R2 construction workers will also be revoked.” This 10% rule thus creates some pressure on employers to ensure that they have higher-skilled workers on their payroll.

MOM provides several pathways for a worker to become an R1 higher-skilled worker (see this page). Generally, the concept is that the worker should have undergone additional skills training to qualify as one. However, one permitted pathway is simply to pay your employee a fixed monthly salary of at least $1,600. The theory behind this is that if the “market” places such a value on the worker, then he deserves to be treated as higher-skilled.

(We have put “market” in quotes because the job market and salary levels of migrant workers is a highly distorted one; in reality it is not a free market even if Singapore pretends that it is – but that is a separate discussion.)

The latter pathway is poorly designed. It simply refers to the Gross fixed salary (basic salary + fixed allowances) before deductions. It glosses over the fact that employers can write into IPAs all sorts of deductions for unspecified reasons, to reduce the nett salary considerably. One can question whether a worker whose nett market value is under $1,600 per month should similarly be treated as a higher-skilled worker.

In Billal’s IPA, we see that his fixed monthly salary (basic + allowance) is $1,610. That squeaks him over the threshold into R1 territory. As a result, the employer can enjoy a $400 discount on the levy. In addition, it allows the employer to employ nine more R2-grade workers, per the ten-percent rule.

But it looks as if the $400 discount is not good enough for the employer. Written into the IPA is another $400 Deduction for Other. This sum is almost the same as the $500 levy the employer needs to pay for Billal. Nowhere is the purpose of this deduction made explicit, so one cannot say if clawing back the levy cost from the employee was the motive, but since money is fungible, it really does not need to be explicit.

Still, out of diligence, we asked Billal what goods or services (that should have been of benefit to him) he got in return for this salary deduction. Unequivocally, he said, “Nothing.”

Withdrawing consent

In theory, Billal could exercise his right under the Employment Act to withdraw consent for this deduction. In theory, the employer should not penalise him for withdrawing consent.

Billal was in no position to test this theory. Anyone in his position would know that the employer would consider any withdrawal of consent an intolerable affront, never mind the law; Billal would be sacked forthwith, if for no other reason than to make an example of him to other employees who might entertain the same idea.

Billal could file a claim for wrongful dismissal and seek damages. But such a process is going to be lengthy (several months) and its outcome uncertain. Almost surely, a longish and stressful period of unemployment would result. For a foreign worker, looking for a new job is difficult and almost always involves middlemen who charge thousands of dollars. This reality is a consequence of the failure of the authorities to stamp out illegal recruitment fees or to promote a truly transparent job market.

Between, on the one hand losing a job, facing unemployment, and having to pay middlemen for the next job, and on the other hand, accepting the injustice of an illegitimate salary deduction, it’s a no-brainer. Employers know this and that’s why IPAs like Billal’s are not uncommon. The solution is really in the hands of MOM. They need to scrutinise IPA applications and flag up any that are structured suspiciously.

Otherwise, pronouncements about encouraging a higher-skilled workforce and laws about not making employees pay the levy ring hollow.

3081; 9103