Bibba calculating his salary arrears

“Look,” says a volunteer, showing your writer an A4-sized payslip. “It’s the best payslip I have ever seen.”

“It shows a timecard beside the calculations,” he points out.

Indeed, there is a record alongside the salary computation showing what time the employee clocked on and off each day. This allows the employee to check that his salary calculation for the month is accurate, particularly his overtime pay component. Here are the payslips for the months of March, April and May 2025 (click the icons to open bigger images).

The worker, whom we will refer to as Bibba, has with him about a year’s worth of payslips, but March, April and May are enough to illustrate the issues discussed in this article.

Your writer turns to Bibba. “So why are you here at TWC2?”

“Company never pay me,” he says.

Our volunteer chips in, half-laughing. “It’s a beautiful payslip, but it’s all for show. They didn’t pay.”

Bibba had been working with the same boss for over 20 months with salary paid for the first few months, though we didn’t check whether what was paid was fully correct. Those months were anyway beyond the claimable period (12 months back from date of claim). Since November 2024, even as the employer dutifully issued monthly payslips, the meticulously calculated amounts shown on the “beautiful” documents were not actually paid. The men only received dribs and drabs of money ($20 here, $50 there) which were just enough for them to buy food,

A few seconds later, we noticed something else: the numbers there were all wrong! What’s the use of having a wonderful format, yet filled in with arbitrary numbers and calculations performed using formulae contrary to law?

Ultimately, the shortcomings of this company’s payroll management were no different from what we see in so many other companies. However, for a change, we have documentary evidence of these shortcomings, because the format in Bibba’s payslips is so detailed, enabling us to check.

Basic salary

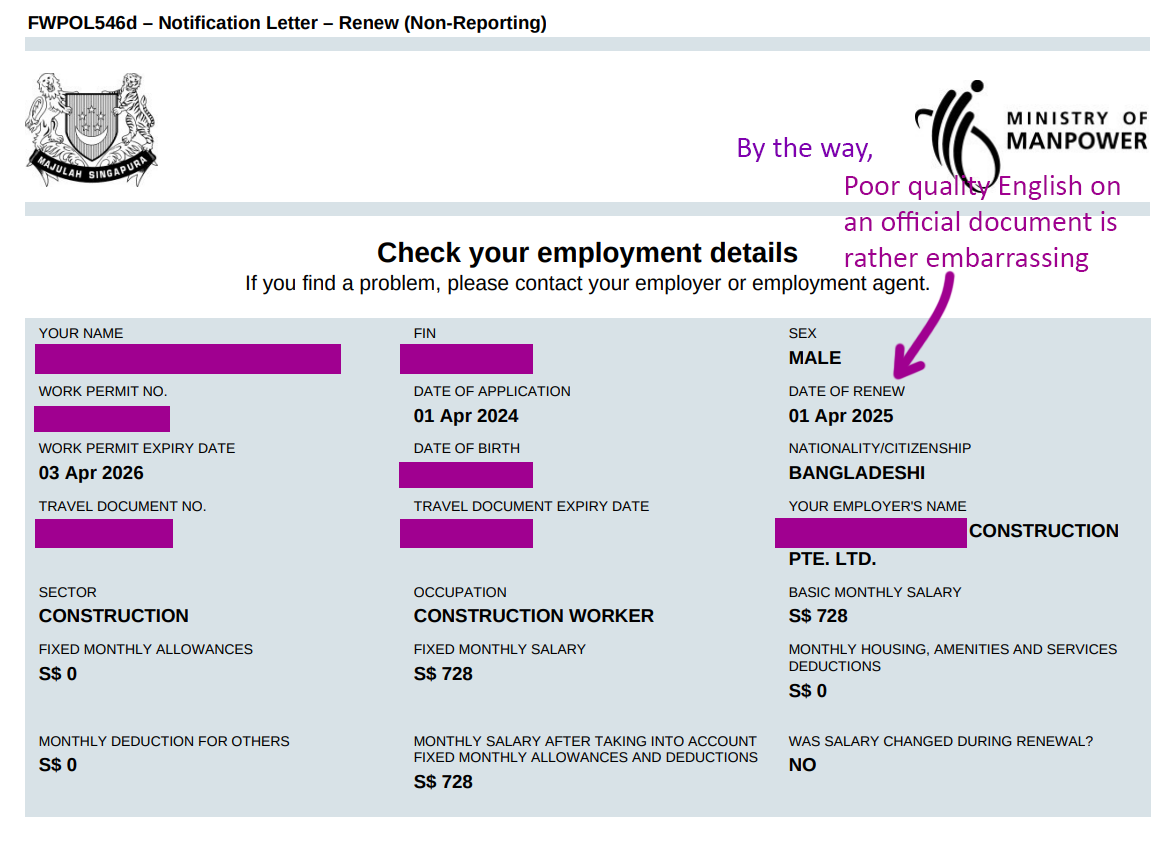

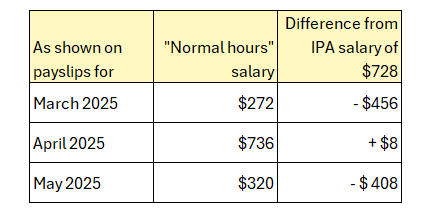

Bibba’s In-Principle Approval (IPA) shows that his monthly basic salary should be $728 per month. This figure was declared by the employer to the Ministry of Manpower, and this figure on the IPA is generally considered the legally enforceable salary absent superseding contracts (none in Bibba’s case). The IPA also states that there are no fixed allowances on top of the basic salary – though occasional or variable allowances are permitted – nor any deductions.

The law is that employers must pay no less than the IPA’s salary and fixed allowances each month.

Yet, in none of the three months (March, April and May 2025) did Bibba’s payslips show a “normal hours” salary of $728. “Normal hours” is generally used synonymously with “basic pay”. The discrepancies were huge.

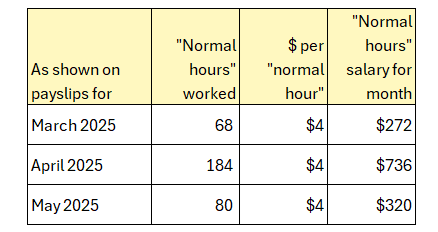

The time log on each payslip permitted us to see how the employer arrived at these hugely discrepant numbers. We could see that whoever was doing the payroll tallied up the number of “normal” hours that Bibba worked each month, and multiplied those hours by $4 per hour.

However, that’s not how basic salary is to be calculated. One is not supposed to multiply the number of hours worked with the hourly rate, because doing so would mean that on days when the worker was not assigned any work (it’s not his fault if the company had nothing for him to do) he wouldn’t be paid. The Employment of Foreign Manpower Act’s subsidiary legislation makes it clear that:

Except where the foreign employee is on no-pay leave outside Singapore, the employer shall, regardless of whether there is actual work for the foreign employee but subject to any other written law, pay the foreign employee not less than —

(a) the amount declared as the fixed monthly salary in the work pass application submitted to the Controller in relation to the foreign employee; or

(b) if the amount of fixed monthly salary is at any time subsequently revised in accordance with paragraph 6A of Part IV, the last revised amount.

– Employment of Foreign Manpower (Work Passes) Regulations 2012 >> Third Schedule >> paragraph 4.

Another section of the same legislation reinforces this. Here it says basic pay should not vary from month to month.

“basic monthly salary” means all remuneration payable monthly to a foreign employee that does not vary from month to month on any basis in respect of work done under his contract of service.

– Employment of Foreign Manpower (Work Passes) Regulations 2012 >> Fourth Schedule >> paragraph 6A.

There was also something arbitrary about using $4 as a basic hourly rate, although by this point in our examination it is irrelevant since this method of calculation (number of normal hours x basic rate per normal hour) is wrong. This rate of $4 is not consistent with a monthly salary of $728!

The Fourth Schedule to the Employment Act sets down a formula for determining the basic rate of pay:

Monthly basic salary multiplied by 12;

then divided by 52 weeks in a year;

and divided again by 44 basic hours per week.

Applying this legislated formula, Bibba’s basic rate of pay should have been $3.82 per hour, not $4. Bibba has no idea why the employer used a $4 rate, even though it was to his advantage.

Overtime pay

It is also mandatory to pay for overtime work at not less than 1.5 times the basic rate of pay for manual workers in jobs like Bibba’s. Unlike basic salary, overtime pay should be calculated using an hourly computation.

Since Bibba’s basic rate of pay (discussed above) should have been $3.82 per hour, his overtime rate of pay should therefore have been $5.73 per hour. For unknown reasons, the employer used a different rate of $6 per hour – which was also, in a small way, to Bibba’s advantage.

Housing deduction

The third oddity about Bibba’s payslip was the way a housing deduction popped up out of nowhere. As evident from the IPA imaged above, there was not supposed to be any housing deduction. Indeed, there wasn’t in several months’ payslips up till March 2025. Then out of the blue, $80 was deducted from his salary as “Housing charge” in the April payslip and again in May.

Bibba says he did not agree to any salary deduction. It’s a completely arbitrary entry made by the employer.

Where’s the money?

As mentioned at the top of this story, ultimately, salary was not paid starting from around November 2024, even as these “beautiful” payslips were assiduously generated month after month. Sometimes, the company manager would give the men $20 or $50 so that they could buy food and not rebel. When we looked at Bibba’s bank statements, we could see these incoming amounts, but nowhere could we see the big amounts that represent salary payments.

One small detail on the payslips is that the Mode of Payment is stated to be cash. We wonder whether it was a simply an unthinking typographical error. Or did it indicate intention to pay in cash, but ultimately was not paid?

There is a third possibility, one taking the form of a dishonest scheme that was intended to work this way: Should the employee (brandishing his bank statements as proof) claim that he was not paid, the employer’s defence would be “But we paid him in cash, and that’s why it does not show up in his bank statements.” However, Regulations require that dormitory-resident workers like Bibba – he was housed in Westlite Dormitory in Jalan Tukang – has to be paid through his bank account. Nonetheless, this neat little scheme to defeat any claim by Bibba might just work because TWC2 has yet to see the authorities penalise employers for paying in cash and flouting the Regulations.

Notwithstanding that, the point is this: we see once again reckless disregard of the rules on the employer’s part.

Bibba’s case is unusual only in that he had these detailed payslips, even though they were wildly inaccurate. In fact, plenty of workers who come to TWC2 for help report that their employers take similar liberties with their salary calculations. These are widespread problems.

16797