The reality of being a migrant worker in Singapore is often harsher than we imagine it to be. The mere basics of receiving a stable salary is not guaranteed. For Turkazul (name changed), this uncertainty is his daily reality.

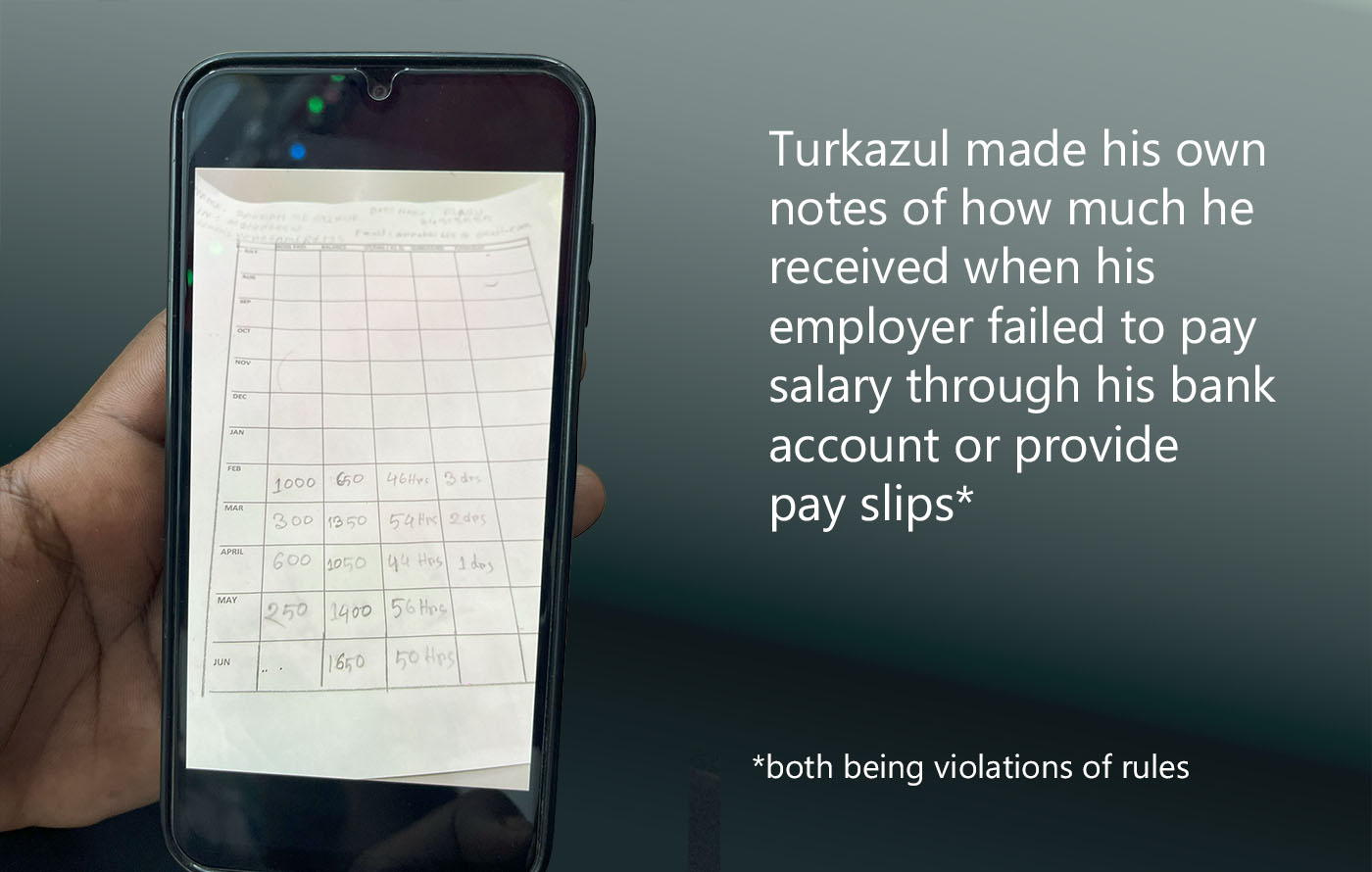

Turkazul transferred to a new company for an electrician’s job in November 2024. Unfortunately, after only three months, his income stream stalled. From the fourth month onwards, he received only ‘makan money’, around $250-300 a month, always in cash. To add to his troubles, he was not given official salary documents. Turkazul tells us that his employer had made him sign blank payslips at the start of his time in the company [see our comment in footnotes]. With all payments done by cash rather than bank transfer, he also did not have a paper trail of how much he had been paid.

When we ask if he had tried to refuse putting down his signature, he tells us, “Anything talking also send back.” It is a line we hear often. If workers challenge their bosses, they are fired and repatriated.

Without any official salary documentation, he only had his own handwritten records to rely on. By his calculations, Turkazul should have received a total of $6,100 over the span of five months, but had only received a total of $2,150 so far.

One worker’s report of wage theft is usually symptomatic of illegal practices that affect many, if not all, workers in the same company. Turkazul’s plight was shared by five other workers, who went together with him to submit a salary claim at the salary claims TADM unit of the Ministry of Manpower (MOM).

At the TADM meetings, Turkazul recounts, it was clear that his boss had not paid his employees via bank transfer. From 2020, work permit holders living in dormitories (now defined as a place of residence with seven or more workers) must be paid through bank accounts. Among the many salary cases handled at TWC2, we have seen a persistent, albeit small, number of employers who have failed to comply with this law.

“Did TADM officer scold your boss?” we ask.

“Ya, officer talking, say to boss: this wrong,” he says.

His boss also presented payslips to the TADM officer, which the workers swiftly decried as false. Turkazul believes the officer knew who was in the wrong.

Change of Employer letters

It is MOM policy that migrant workers with valid employment claims should have the opportunity to look for new jobs without first being repatriated. It is only fair that they should be able to resume gainful employment as soon as possible. MOM granted all six workers Change of Employer (COE) letters allowing them to look for new jobs despite the fact that their salary claims were still in progress.

While this may look like a positive outcome, it’s only the beginning of yet more uncertainty. COE letters do not guarantee a new job, they only allow workers to start looking for new jobs. More critically, they have a validity period of just two weeks. How is anyone to find a new employer within two weeks? If no new job is found within the validity period, the worker still has to go home. For Turkazul, who borrowed a total sum of $10,000 to come to Singapore, half from a loan from a bank and half from his family, going home is not an option.

Turkazul’s boss flouted the law, falsified documents, and failed to pay his employees for their labour. Sadly, justice is not guaranteed with TADM, who play the role of mediators between workers and employers. TADM is not an enforcement body charged with a mission to get workers the full sum they are rightfully owed. Instead, they are focussed on getting both parties to settle. And since employers are often not compelled to pay the full sum owed, settlements are often partial.The alternative, should no settlement be reached, is for workers to bring their employer to the Employment Claims Tribunal, but that is another long and tedious process that some workers do not have the resources to pursue.

Turkazul’s story is unfortunately not unique. Wage theft and delayed wages are common amongst the migrant worker population in Singapore. MOM’s 2024 Employment Standards Report revealed that the incidence of claims from migrant workers is higher than that from local employees. Over 5,000 migrant workers filed a claim last year, pushing up the incidence rate from 3.91 per 1,000 foreign employees in 2023 to 4.64 in 2024.

Yet, 5,000 is a conservative estimate, in TWC2’s opinion. Many more migrant workers do not file claims for a variety of reasons, such as

- new to Singapore, not aware of how to file a claim;

- no evidence in hand, discouraged from even attempting to lodge a claim and suffering the long process that results;

- prefer to remain on good terms with their bosses in the hope of getting amicable transfer letters from their bosses and then moving on to new jobs.

Since such salary violations by employers are clearly against current regulations, one might expect strong enforcement to play a role in minimising transgressions. The reality, however, is that enforcement remains weak. Without deterrence, employers do not feel afraid to delay or evade salary dues and the burden ultimately falls on workers who struggle to prove their claims while navigating debt, family obligations and a foreign environment.

Behind every statistic is a man like Turkazul, who simply came to Singapore in the expectation of a better life for himself and his family, only to be met with loss and frustration.

It is not common, but every now and then, TWC2 comes across a case where migrant workers say their bosses demanded that they pre-sign payment vouchers (usually left blank) that would later be used as evidence of salary payment. Sometimes employees are misled as to what these blank pieces of paper would be used for; other times, the workers would have a suspicion that they would later be used to “prove” that they had received their salary. Yet, many would feel unable to resist their employers’ demands to sign, because they would have paid thousands of dollars to secure these jobs. They might feel it was better to sign and hope that salaries would later be paid, than to refuse to sign and surely lose their jobs.

These earlier articles illustrate the different ways this plays out:

This is why it is important that salaries should always be paid through bank accounts. Doing so creates an objective record of how much was actually paid.

But merely having such a rule on paper isn’t enough. It must be enforced. Any employer who fails to do so should be prosecuted, otherwise there is no incentive to follow the rules when flouting them can result in getting away with stealing employees’ salaries.

It should also be noted that even this rule only applies to certain categories of migrant workers. Many Work Permit holders do not reside in dormitories and they do not have to be paid electronically. This lacuna must be fixed.

16597