Diners in a hotpot restaurant (often referred to as a steamboat restuarant in Singapore).

A hotpot restaurant worker comes to us for help over unpaid overtime. But how much is he actually owed? Whilst Work Permit holders can estimate how much they should be paid for overtime work, most do not know how to calculate it with any precision. Doing so requires deep familiarity with employment legislation and its many clauses.

TWC2’s case officers, on the other hand, are good at this. We have handled literally thousands of cases.

The worker – Jimmy is how we will call him – was further discouraged by the Tripartite Alliance for Dispute Management (TADM), the unit located in the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) that handles salary claims. He told us in one of the earlier visits to TWC2 that his TADM officer offered the opinion that he had no case.

This didn’t make any sense. He knew he worked more than 12 hours a day. He also had only two rest days a month. Yet, every month he was paid a flat rate of $1,800 which was in the same ballpark as what he understood his fixed monthly salary to be. Fixed monthly salary excludes overtime; the latter has to be treated as a variable component of salary on top of the fixed components. Moreover, by its very nature, overtime hours are extremely unlikely to be exactly the same from one month to another, so the overtime pay component tends to go and down. It does not present as a flat rate that remains constant month to month. Yet, Jimmy’s pay packet remained constant.

‘Ballpark’ should strike readers as an interesting word to use. Doesn’t Jimmy know exactly what his basic salary or fixed monthly salary is? Isn’t it documented somewhere?

And that’s the crux of the problem in this case. The numbers in his documents are all over the place. How is he to make a cogent case? If not for the experts at TWC2, he would have had no way to contest the TADM officer’s opinion that he had no case. TWC2 not only worked out the precise and evidence-supported claim amounts for him, we also helped him frame persuasive arguments from the mess of contradictory documents.

This is the story of how his case was built.

The IPA and the employment contract

Before starting work with the hotpot restaurant in downtown Singapore, Jimmy had received an In-Principle Approval letter (IPA) from MOM. The letter indicated the ministry’s approval of his Work Permit, but also contained details of the salary. These details would have been provided by the employer when submitting the application to MOM; they are supposed to represent the private agreement reached between parties as to the terms of employment.

In the IPA, Jimmy’s basic salary was stated as $1,000, with an additional fixed monthly allowance of $1,000. The fixed monthly salary was thus $2,000. No deductions were stated on the IPA.

However, about three or four months after starting work in November 2023, the employer made him sign a new contract. Jimmy wasn’t even told that it was a new contract. He was given the impression that the papers presented to him for his signature were some forms that MOM required. Nor was he given a copy of whatever he signed, so he never got a chance to read it.

After Jimmy filed a claim at TADM for unpaid overtime, the employer presented the contract to justify their position that JImmy had been correctly paid. Jimmy was taken aback. He had no idea there was a contract, nor what the details in it were. This is contract substitution – an internationally recognised indicator of forced labour. We wrote about this in the article Scams and substitutions, case #2 or 3.

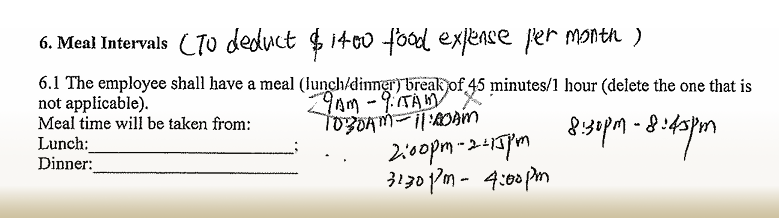

The contract was poorly drafted. The dollar values in it were handwritten, often as side-notes to the main text. For example, one portion said his basic salary would be $1,600 per month with an allowance of $200 per month. However, ‘$3,200’ and ‘$1,400’ also appear alongside, though what these numbers represented was not spelled out.

It is notable that Jimmy was paid a flat rate of $1,800 a month, which coincidentally or not, is $1,600 + $200. The implication would therefore be that he was paid just the basic and allowance as per the contract. But these figures are different from the those on the IPA.

A little further down, there is a clause about overtime pay, and another about work on Sundays or rest days. The language of these clauses follows the Employment Act closely.

Then, the contract has working hours.

It is noteworthy that the hours were handwritten and apart from the printed text. Was the notation about hours there when the contract was signed or was it added after Jimmy had signed it (though he didn’t know he was signing it)?

Another handwritten notation made reference to a $1,400 deduction for meals provided. Below, we will show how Jimmy, on our advice, contested this.

At this point, while trying to press his claim at TADM, how was Jimmy to make sense of all this? Should he base his claim on the IPA or the contract? In any case, he didn’t have any time cards that could prove that he worked overtime or on rest days. Perhaps this was why the TADM officer told him he didn’t have a case. It was a good thing that he came to TWC2 for help.

Building a case

TWC2 case officers scrutinised the various documents closely, together with Jimmy’s bank statements to verify that he had not received the correct salary. With the employer not agreeing to any settlement at TADM’s mediation stage, Jimmy’s case was definitely headed to the Employment Claims Tribunal (ECT). We metaphorically peered into the hotpot to see what ingredients there were amidst all the confusing and conflicting materials to plot a path forward. We had to find cogent and evidence-based lines of argument and write everything up for him before the tribunal’s hearing date.

We advised him that, contrary to his initial position taken at TADM when he asserted his claim on the basis of the IPA’s details, at ECT, he should ground the claim on the contract, however unfair and unethical it was in the way he was made to sign it a year earlier. The details on the contract were more helpful to him, though the employer didn’t know it yet.

Jimmy would have to demonstrate the following elements at the tribunal:

- What the correct basic salary should be;

- What were the overtime hours he worked, and therefore what the overtime pay should be;

- What were the rest days he worked, and therefore what the rest day pay should be.

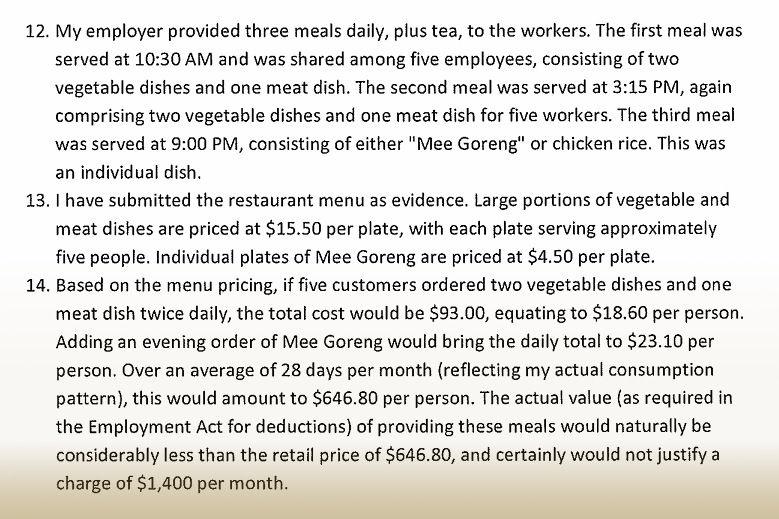

We could also anticipate the employer asserting that they had a right to claw back $1,400 from Jimmy’s salary as the cost of providing him with meals. It was necessary to prepare a defence for this.

The contract stated the basic salary to be $1,600 per month (see first extract imaged above), much higher than the basic salary of $1,000 in the IPA. Moreover, the contract itself reiterated (in a footnote) the provision in employment law that overtime pay should be 1.5 times the basic rate of pay. These details would be helpful to Jimmy.

But how many hours? Without time cards, this might be a difficult hurdle. However, the contract itself contained a notation that Jimmy had to work between 9am and 10pm each day (see the second extract imaged above). These were almost exactly the hours that Jimmy claimed to have worked. On this basis, he was working about 3.5 overtime hours daily.

The same with rest days. The contract itself had notation that spelled out his obligation to take only two rest days a month. Under the Employment Act, an employee is entitled to one rest day per week (four or five a month), and so it is obvious that Jimmy had to work on the other rest days. And obviously, he should be paid for those days.

How about the $1,400 deduction for meals? Two arguments could be made to contest this. Firstly, the figure “$1,400” was handwritten into the contract. Jimmy said he didn’t see it; was the figure even there on the day of signing?

The following extracts are from the court submission that Jimmy filed:

The Employment of Foreign Manpower Act requires any increase in salary deductions to not only have the employee’s prior consent in writing, but the deduction has to be notifed to MOM in advance before it can take effect. In this case, a check with MOM’s data system shows that there was no notification about it.

Moreover, the Employment Act says that any deduction amount must be commensurate with the cost of the benefit provided. An employer cannot provide employees with, say, a bar of chocolate worth $2 and then deduct $100 from the employee’s salary for doing so. We assisted Jimmy in writing the rebuttal to this deduction, using none other than the restaurant’s own menu as the starting point.

Verdict

The above shows how invaluable assistance by TWC2 is. No low-skill, low-wage worker could have framed the above arguments himself, let alone draft the written submission. Singapore’s court system requires all submissions to be written and filed electronically – these technical demands alone would seriously disadvantage the typical Work Permit holder.

But did these arguments carry the day?

The tribunal hearing was held over Zoom on 8 August 2025. Three weeks later, parties are called together again, also over Zoom, to hear the judge’s decision. It doesn’t take long, just 15 to 20 minutes. Jimmy is awarded his claim in full, totalling $18,400. The employer is given one week to pay up.

Jimmy is all smiles as he emerges. Eight harrowing months he has endured. Eight jobless months too, because he was put on a Special Pass after his Work Permit was cancelled, and the Special Pass does not permit the holder to take on any employment. Strictly speaking, TADM could have given him permission to seek a new job even while the case ground on, but in Jimmy’s case, his TADM officer did not agree to this. According to Jimmy, she took the position that since she did not believe he had a valid case, she was not going to issue him with a permission letter (She did however say that if he won at ECT, she would reverse herself).

“I borrowed $2,500 from friends to survive these months,” he tells TWC2. “Now of course, I have to pay them back.”

Lengthening wait for ECT

As an aside, there’s something we have noticed about Jimmy’s and other workers’ ECT cases. They are taking longer and longer to get court dates. In Jimmy’s case, the tribunal hearing was only held about eight months after he filed his salary claim. This seems to be the norm now when it used to be six months or less.

There is an increasing number of salary claims being filed, that may be part of the reason. But we also wonder if there are capacity contraints in the courts.

This is no inconsequential technicality. It has real impact on already vulnerable people. Claimants often remain jobless while waiting for case resolution.

We remind Jimmy that he should go back to the TADM officer and ask her to live up to her word that should he win at ECT, he would get permission for a transfer. (Update: he was given permission for transfer).

He is naturally eager to share the good news with his wife and two children back in Myanmar, and so we don’t want to detain him any longer than absolutely necessary, but before he leaves, he says, “TWC2 helped me a lot,” followed with a question: “Now, how can I help TWC2?”

15783