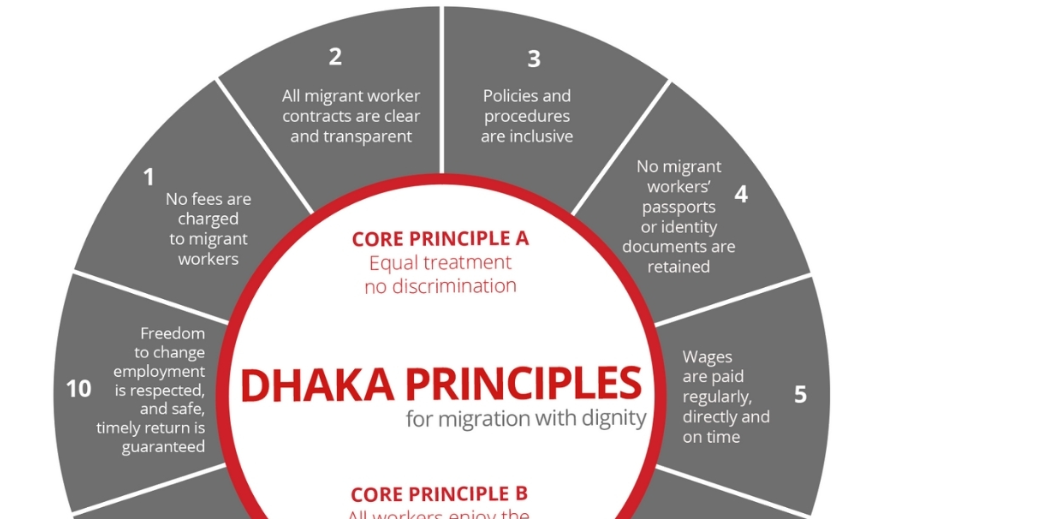

The very first of the Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity says “The employer should bear the full costs of recruitment and placement. Migrant workers are not charged any fees for recruitment or placement.” Expanding on this, it explains:

Migrant recruiters frequently charge fees to workers for recruitment and placement. Placement fees may include travel, visa and administrative costs, and other assorted unspecified ‘fees’ and ‘service charges’

It is worth noting that the Dhaka Principles are phrased in a way that indicates that what recruiters do (and charge) is also the responsibility of employers. This is right. After all, employers choose which recruiters to work with and therefore should be held accountable for their recruiters’ actions.

Major international companies often want their Singapore suppliers to abide by the Dhaka Principles. The reality however is that these suppliers, who are the employers of migrant workers, are often reluctant to move with the times.

One way of deflecting scrutiny is when employers interpret the Dhaka Principles narrowly; they say, “but we didn’t take any money even if the recruiter did.” This does not meet the standard required by the Dhaka Principles.

Dibavash’s story shines a light on what really goes on. In this story, fees were charged to the worker. More importantly, the employer definitely knew about it. Moreover, the employer is a contractor for Seatrium, a big marine engineering and shipyard company, and one which has declared its adherence to the Dhaka Principles: “Our approach to human rights is informed and guided by the Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity.”

Getting the job

It’s the second quarter of 2025. Dibavash (not his real name) has been home in Bangladesh for eight months already after a six-year stint in Singapore. There’s a bit of a story about how that job ended. He had gone on home leave to see his newborn son, but the happiness of the new father was crushed when he suddenly got news that his Work Permit had been cancelled without warning while he was out of Singapore,

Dibavash doesn’t seem bitter in recounting that. He just had to move on, he says. Very stoic of him.

He came into contact with a recruiter in Bangladesh named Monirul Islam, and from the beginning, it was more than clear that payment would be needed, though the amount seemed to have been left a little vague. This might have had something to do with the fact that Dibavash was an experienced worker, and so the set rates that normally apply to fresh new workers would not apply, and the rate for someone like Dibavash might be negotiable. Monirul Islam operates out of a training centre, though Dibavash did not need to attend any training there.

It is common for shipyard contractors to link up with training centres in Dhaka, because these centres can provide the trained workers the contractors (employers) need. These centres also act as recruitment hubs, but what this means is that employers have long-standing relationships with recruiters based in these training centres; they do not flit from one recruiting agent to another. Long-standing relationships imply a familiarity with the recruiters’ operating models.

On 16 June 2025, Dibavash attended a job interview at the training centre in Dhaka. Interviewing him were two men who (according to Dibavash) had flown in from Singapore. Dibavash would later refer to one of the interviewers as the boss of the Singapore company he would later join, and which we refer to here as Raptor Mim. Because the position Dibavash was interested in was a driver’s job, much of the conversation was about his driving skills and experience. There was no discussion of recruitment fee. However, the salary was discussed and a figure of $704 per month in basic salary was agreed upon.

We would later see monthly deductions of $130 written into his In-principle Approval letter, but we’re not clear if this was discussed during the interview or inserted later.

Wrangling over the fee

After the job was offered to Dibavash, the recruiter Monirul Islam asked for three lakh Bangladeshi taka (300,000 taka) in recruitment fee. This would be equivalent to about $2,800 or $2,900. Dibavash refused to agree to this. After some back and forth, the figure was reduced to 250,000 taka. Dibavash still refused.

Then out of the blue, the same boss of Raptor Mim called from Singapore to try to resolve Dibavash’s position regarding the fee. Finally, the boss agreed that after Dibavash has joined the company, he would give Dibavash a $400 refund. With that, Dibavash agreed to accept the job and soon after, paid 250,000 taka (roughly $2,400) to Monirul Islam.

What’s obvious from the above sequence of events is that Monirul Islam must have shared details of the asked-for fee and Dibavash’s refusal with Raptor Mim, thus prompting the call from the boss. In addition, what’s also suggested from the above is that a part of the fee was going to go to the boss, which is how the boss could have agreed to part with $400 (from his cut of the fee) as an inducement to close the deal.

It is this kind of incestuous relationship between recruiter and employer that the Dhaka Principles try to address. It is artificial to separate the employer’s responsibility from the agent’s. “Migrant workers are not charged any fees for recruitment or placement” should mean exactly that.

Dishonoured

The $400 rebate never materialised. That would prove to be the first of several bones of contention. Two months after joining the company, the boss told Dibavash his basic salary would be reduced to $660 a month – another bone of contention.

The boss also said the company didn’t really have much work for him, which leads one to wonder why the company even hired him in the first place. Dibavash then said the company should give him a letter permitting him to seek a transfer job. The boss said okay to that, but a month on, the letter still had not materialised.

Dibavash reminded the boss about the promise to give him a transfer letter. The boss got angry and sacked him.

The eve of departure

We have to turn the conversation back. Dibavash is too quick to come to his present predicament of losing his job though it is understandable since it is the most pressing issue on his mind right now.

We ask him to think back to the recruitment process. That’s when he says, “Oh, and before come one day, they ask me go to training centre.” He’s referring to the day before he came to Singapore (he flew here on 10 July 2025). The training centre was where Monirul Islam was based.

“The IPA and ticket… before come one day, they give me IPA and ticket,” recounts Dibavash of the eve of departure, as can be heard in this audioclip:

“What about your passport?” we ask.

“Passport also give me,” Dibavash replies. He had earlier been required to deposit his passport with Monirul Islam.

“Did they ask you to sign any document when you were there?”

“Yes. They make paper for me, without money I come Singapore.” Dibavash explains.

We have to be sure we understand correctly. “The paper said…”

“Without money I come to Singapore.”

“… that you did not have to pay any money to come to Singapore. Is that what the paper said?”

“Paper say I free coming Singapore.”

He had little choice but to sign the document since he had already paid the fee.

“Because that time, no more time. Everything I pay money, then before also never tell me anything. Before come one day only, tell me suddenly.”

Having paid the fee, Dibavash had no choice but to sign the document as demanded.

“That’s why I cannot do anything.”

However, in the eyes of the recruiter and employer, the forced document was not enough.

“Just before flight date, flight that day they tell me suddenly, they make paper for me, ‘You sign then go’, then make video also for me.”

That’s a new element in his story – though we’ve heard similar accounts from other shipyard workers – and we had to be sure we understand correctly.

“Sorry, what? Make video?” we check. “They asked you to appear in a video?”

“They first teach me how to tell this video,” Dibavash explains.

“What did you have to say in this video?”

“They teach me ‘You come Singapore without money, we never take money from you.’ Actually, before date never tell me like this.”

Do you hear from the audio clip how his tone of voice is subtly changing? Just recounting the experience makes him mad all over again, which of course he has every right to be.

16996