Caption for photo

This is the fifth and last in our series of articles commenting on the results of the Ministry of Manpower’s (MOM’s) Migrant Worker Experience and Employer Survey 2024. The results were released in the third week of August 2025. In this Part 5 , we will focus on passports.

Passports

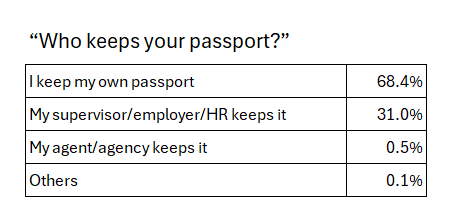

Replies to the questions on passports do not paint a good picture. Only 68.4% of Work Permit holders said they got to keep their own passports. Frankly, there is no acceptable reason for anyone else to be holding on to workers’ passports – not employers, not agents. The figure should be 100%.

To retain another person’s passport without compelling reason to do so is a criminal offence. Section 47(5) of the Passports Act 2007 says:

(5) If —

(a) a person has or retains possession or control in Singapore of a foreign travel document; and

(b) the person knows that the foreign travel document was not issued to him or her,

the person shall be guilty of an offence and shall be liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding $10,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years or to both.

MOM itself states very clearly on its website that “According to the Passports Act, it is an offence to keep or withhold any passport which does not belong to you”, and that “Employers should not keep the passports of their migrant workers or migrant domestic workers”. Therefore, what MOM’s survey has found is that over 30% of workers have their employers (or agents) breaking the law.

The question that needs to be put to MOM is: What are you doing about it?

Who is the ‘migrant worker’?

MOM’s survey report speaks of the ‘migrant worker’. The survey’s scope was limited to Work Permit holders in non-domestic sectors. In other words, domestic workers are not part of this discussion.

MOM’s preferred “softly softly” is alas all too evident from the second question in the survey: “Have your passport been returned to you when you asked for them?” This question should never have been asked. Agreeing to return the passport when asked is no defence against the offence of taking it in the first place. It’s like asking shop owners whether, when someone has shoplifted an item from their shop, the person has returned the item when requested to do so. If that’s how the issue is framed, then one can accuse the authorities of looking away when the law is violated.

Meal arrangements

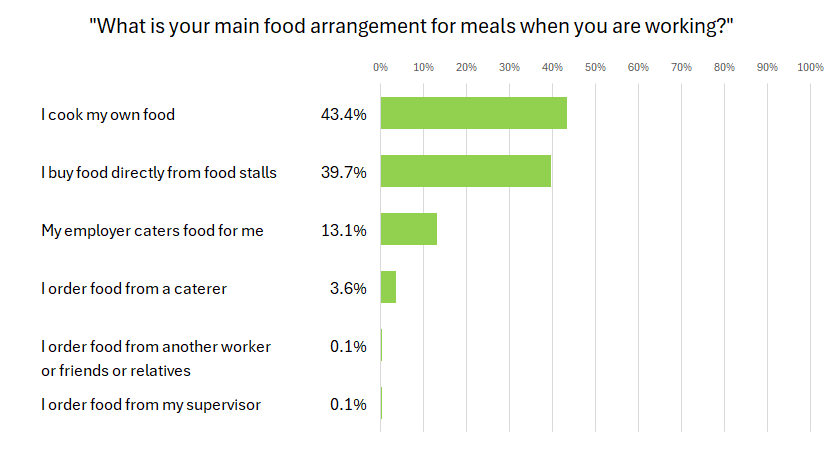

We found the replies to the question about meal arrangements rather hard to believe, contradicting what many of our clients tell us.

As can be seen from the graph, only 16.7% (13.1% + 3.6%) of survey participants mentioned catered meals. That’s one in six Work Permit holders, and is completely at odds with what our clients have been telling us for years. Workers in the construction, marine and process sectors (CMP) are almost all living in mass dormitories, for which catered food is, by far, the most common arrangement.

There were 456,800 in CMP out of 864,300 in non-domestic sectors, meaning that CMP workers make up 54% of all non-domestic Work Permit holders as at December 2024. We reckon that at least four-fifths of them are on catered meals. So, logically, the survey should be getting a figure of around 45 -50% saying “catered meals”, instead of the report’s 16.7%.

From a distance, it is not possible to explain why there is such a difference. Although one scenario may be that CMP workers were under-sampled, yet in the introduction to the report (paragraph 1.2) it did say that the researchers were careful about sectorial weighting.

Perception of MOM and workplace conditions

Before commenting on the next question, it may be important to note a sentence in the report’s end-notes, under Methodology:

The survey on migrant workers was a self-administered survey in English or the native language of the respondent. In cases where the respondent requested for assistance to understand the question, the interviewers explained the questions to the respondent.

The picture this paints is that of an interviewer standing close by the worker who had agreed to do the survey. The concerns that arise include:

1. How did the interviewer introduce himself or herself?

2. What was explained to the worker regarding who (or which organisation) was behind the survey?

3. Was it mentioned that the survey was being done on behalf of MOM?

4. Even if MOM was not mentioned, what assumptions might the survey participant have made about who was behind this exercise?

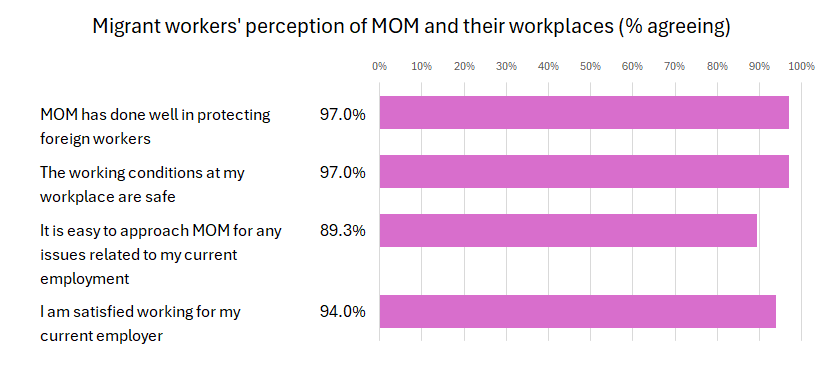

These concerns come to the fore when we look at the next set of data. The numbers glow so much, they are nearly radioactive.

There is plenty of literature that describes how migrant workers in Singapore “know their place”. We can even see it in daily life, such as on trains when they avoid sitting down beside locals – not that they don’t like locals, but they are aware that the locals might not like them to take the seat beside. In the same way, migrant workers may make the default assumption, unless they are already familiar with and trust the organisation behind the survey, that anything they say in a survey may get back to the government and jeopardise their continued career in Singapore. It costs nothing to give answers that interviewers might want to hear, but it can be extremely costly to themselves to be carelessly honest.

Did that happen here?