File photo: a migrant worker carries a take-away meal

Twenty-four hours was all it took for Rafiqu’s life to turn upside down. First, his work permit was cancelled by his employer and he was to be repatriated. However, Rafiqu was still owed his salary so he filed a salary claim with the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) and obtained a Special Pass. Having a Special Pass would allow him to stay in Singapore for the duration of the claim. The same evening, he was kicked out of his dorm.

On 17 May 2024, MOM published on its website a “fact check” statement that accused us of inaccuracy and misinformation in this article. In the second Post-Script below, we will address the points they made. Readers will be able to see that MOM effectively confirmed the same information we provided in this article.

Rafiqu’s problems began in mid-January 2024, when he got into an altercation with a co-worker at his work site. According to Rafiqu, he was beaten up and called the police. His boss showed up shortly after the police arrived and was furious that Rafiqu had made a scene at the worksite by calling the authorities.

Days later, on 24 January at around 7pm, his work permit was cancelled and he was asked to pay $700 for causing an issue at the worksite. Rafiqu also found out from his agent shortly after that the company planned to send him back to Bangladesh the next day. This news unsettled him as he had not been paid four months of salary amounting to about $4,900.

This total comprised (1) overtime pay and allowances for October and November 2023, as Rafiqu was only paid his basic salary of $450 during those two months; and (2) salaries for December 2023 and January 2024, including overtime pay and allowances.

Rafiqu had not worked long at this company, having only started with them on 17 October 2023. However, Rafiqu, a carpenter by trade, had been working in Singapore since 2008.

Thrown out of the dormitory

Once he filed a salary claim, things escalated rapidly. At 12:04am on 25 January, he was escorted out of the dorm by the company supervisor and a security officer, along with his luggage and other personal belongings.

Stranded and homeless, Rafiqu spent the night at a bus stop on the first night. Rain was pouring down.

Later that morning, Rafiqu went to the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) to file a salary claim and was issued a Special Pass by 3pm. According to him, the MOM officer also spoke to the company, who then reversed their position and agreed to continue housing Rafiqu in a dorm. Through MOM, the employer communicated that Rafiqu was to return to his worksite in Jurong West, where the company’s temporary office was located. From there, a lorry would take him to his new dorm.

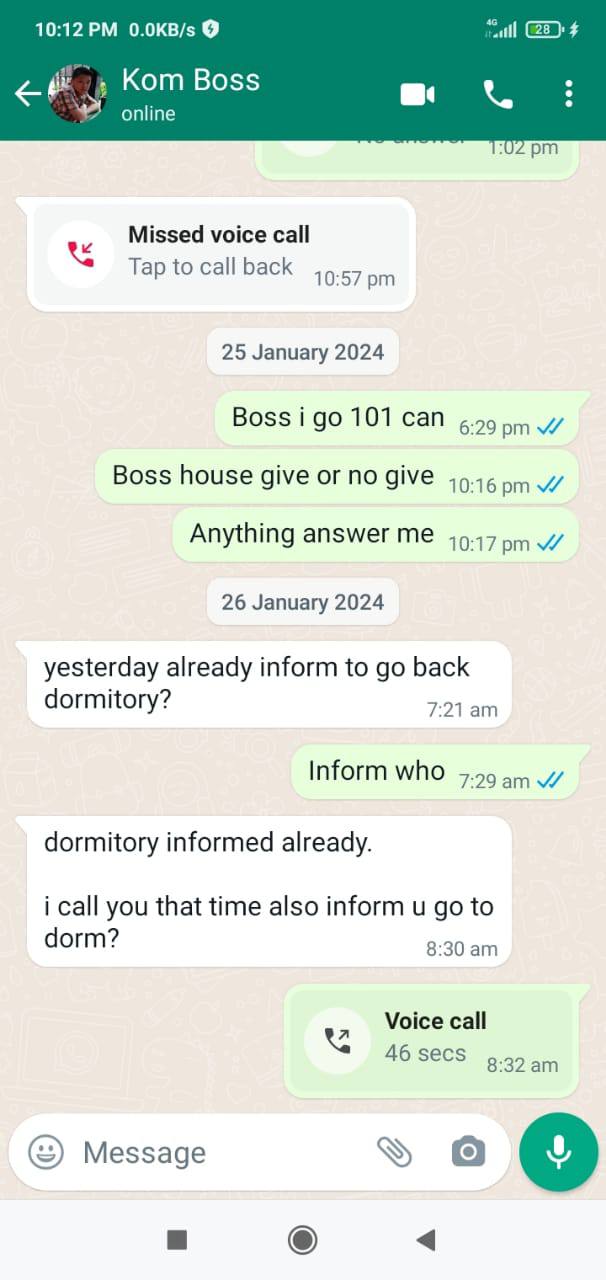

Rafiqu arrived at the worksite around 7pm and called to inform his boss, who instructed him to wait at the location and that he would get back to him shortly on his living arrangements. However, Rafiqu’s hopes were crushed when his boss suddenly became uncontactable, despite the worker’s efforts to contact him until 11pm.

Equally fruitless was Rafiqu’s attempt to reach the Tripartite Alliance for Dispute Management (TADM) for help. TADM is the unit in MOM that handles salary claims, and an officer there was Rafiqu’s main contact point at the ministry

Once again and for a second night, he was homeless, standing at a shelter outside the worksite the whole night with his luggage and personal belongings.

‘Desolate’ and ‘helpless’ aptly describe how he felt those two nights. Rafiqu added that he felt restless, sad, dizzy from the stress and hunger, and experienced pain in his chest from fear and anger as he did not know how to proceed.

“When I listen my permit cut and dorm already out, I feel heart inside very no good…How to makan? Makan also no have. Whole two nights many many mosquitoes. Suddenly I think I fall down, I unhealthy, I scared so many many. That’s why my head also rounding (dizzy), I do what? This time I don’t know,” he explains.

Again

Just as he was returning to MOM on the morning of 26 January, Rafiqu received a text from his boss informing him that arrangements had finally been made for him at a new location. He explained the new developments of his situation to the MOM officer, who contacted the company, perhaps to verify the news. However, as explained further on, the so-called arrangements remained unclear till later in the day.

While the MOM officer felt sorry about his plight and offered him biscuits, instant noodles, and coffee to quell his hunger – an act he appreciated – Rafiqu said he did not feel any real compassion from MOM. In fact, they were ‘mechanical’ in how they treated him, an opinion formed from how they explained to him (that day and other days) that while the law requires employers to house and feed workers, beyond that there was nothing more they could do.

It wasn’t until 3pm on 26 January that Rafiqu received details of where to go, at last confirming that there was indeed a bed for him. He arrived at the worksite at 5pm via public transport and waited until 6pm for his boss to appear. Rafiqu had been told that a lorry would fetch him from the worksite to the new dorm.

He waited at the worksite. At 8.30pm, his boss informed him that there was no space in the dorm, and that his agent had suggested that Rafiqu find his own accommodation in Little India. The boss would give Rafiqu $20 per night for whatever bedspace he could find.

By then, Rafiqu had not eaten anything substantial for two days and he was at his wits’ end. Through a friend, he sought help from TWC2. We quickly moved him into our temporary shelter, where he would stay for the following five nights. During that period, he was still in touch with MOM, and the ministry with his boss, but Rafiqu had the impression that the boss was ‘dangling him around’, without any intention to resolve the issue.

Two-and-a-half hour trip to collect meals

While he was staying with us in TWC2’s shelter, we provided him with food too.

On the fifth day of his stay with us, MOM informed him that his employer had finally arranged for him to stay at a dorm in Tuas. Rafiqu asked about the meal arrangements there. MOM reassured him that the company would arrange for all his meals, but added that the meals were to be picked up at the company office at Gambas Avenue. Rafiqu would also be paid an allowance for public transport.

In theory, well and good. In practice, it would be absurd. Gambas Avenue, Rafiqu estimated, was two and a half hours’ roundtrip by public transport from the dorm in Tuas.

Naturally, Rafiqu pushed back, saying it would not be feasible for him to travel back and forth three times a day just to collect his meals. The MOM officer’s response that was the ministry was unable to take further action as that was the arrangement his boss had made. The suggested alternative was that Rafiqu should travel just once each morning and back in the evening, squatting in the office the whole day (each and every day) so that he could have all his meals.

“I say Tuas to company office two-and-a-half-hours long far, how can go? Every day I go after I unwell. [MOM officer] say this one no choice, the company boss arrange food, you must go and take.”

While all that was happening, Rafiqu was met with yet another hurdle when he arrived at the Tuas dorm. He was told that there was no bed booked under his name. The “arrangements” were once again less than what appeared to the eye. Rafiqu informed his MOM officer overseeing his case. It took an hour before the officer came back to him to say things had been sorted out. Rafiqu was allowed into the Tuas dorm.

He did not eat that night.

The next morning, Rafiqu made the gruelling journey to Gambas Avenue to pick up his breakfast, and went back in the afternoon for lunch. He was only offered breakfast and lunch the first two days. Dinner was out of the question as the office was closed by the time he arrived. Rafiqu called the office staff, who explained that the matter was out of her hands and he would have to take up the matter with his boss or complain to MOM.

By then, the boss had ceased all contact with Rafiqu. His only solution was to go hungry every night as he did not have any money for food. Unable to receive proper help nor collect his food, Rafiqu felt nobody was paying him any attention. With the office closed over the weekend, there was no point even making the trip. He borrowed money from a friend to buy food on Sunday (4 February), and had one meal.

Around that time, Rafiqu decided that it wouldn’t mean much to bring up the food issues with MOM again, since it was almost certain that officer’s response would be along the lines of: this is the arrangement made and it has to be followed.

He adds, “I go MOM I say after no benefit coming because MOM officer say this one company rule. Company arrange food, you unhealth you go see doctor…You must be go office and then collect then eat.”

Despite having worked in Singapore since 2008, this is the first time Rafiqu has experienced such an issue. He has worked for four companies in total and was paid regularly, housed in a company dorm, and had money for catered daily meals.

Sole breadwinner

While working, Rafiqu was able to remit $300 a month to his family for food and school fees. With his salary claim and him being unable to work due to the Special Pass, the family’s finances have dried up. The 40-year-old worker has several mouths to feed. His three children are 11 years old, six years old, and six months old. His father and mother are 80 years old and 60 years old, respectively, and his mother-in-law is about 50 years old. Rafiqu’s wife is in her late twenties.

His wife and children have called to ask him for money but Rafiqu is helpless every time. “Now I say company salary no give…how I send you money? That time my children also cry, my father mother cry, my wife cry…”

It has not helped that his agent has been demanding that he resolve this amicably with his boss or he would be blacklisted and never be allowed to work in Singapore again. (This is a bluff since employers do not have the power to blacklist migrant workers). This only added to the stress Rafiqu is currently experiencing, leading to sleepless nights.

“I feel this one mentally problem, every night sleep no coming, I tension. I again no come back Singapore, my balance also money no have, after I how to do, how to maintain family…” he said.

Since this interview, Rafiqu has managed to find a new job and is now properly housed. He is able to get his own meals with the new job’s earnings. His salary case remains pending, and TWC2 continues to assist him over it.

22 May 2024

On 17 May 2024, MOM published a statement on its website saying that this article had “inaccuracies and misinformation on the Ministry of Manpower and the Tripartite Alliance for Dispute Management,” and that “TWC2’s article cast aspersions on the professionalism of MOM and TADM officers who support workers with their claims.”

Indeed, we do think that the response of the officers in this case was less than satisfactory. The worker himself also thought so and said so.

MOM took issue with two points we made.

In its statement, it wrote: “The above is a misleading account. On 25 Jan 2024, Rafiqu went to MOM Services Centre to report that he had been asked to leave his dormitory. TADM referred him to MOM’s Assurance, Care & Engagement (ACE) Group for housing assistance. His accommodation was sorted out by the next day.”

What did TWC2 write? We said (above), “Later that morning, Rafiqu went to the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) to file a salary claim and was issued a Special Pass by 3pm. According to him, the MOM officer also spoke to the company, who then reversed their position and agreed to continue housing Rafiqu in a dorm. Through MOM, the employer communicated that Rafiqu was to return to his worksite in Jurong West, where the company’s temporary office was located. From there, a lorry would take him to his new dorm.”

As readers can see, we did state that there was an initial resolution of the housing problem the next day, but our story goes on to detail how it all unravelled within hours. It seems to us that we have been more transparent about what happened, about the whole picture, than MOM would like us to be. Now, why does MOM take issue with our more complete and transparent account?

Interestingly, MOM’s own statement hints at how the immediate resolution of the housing problem didn’t stick. MOM wrote: “Between 25 Jan and 28 Feb 2024, there were multiple interactions between Rafiqu, company representatives, and MOM, to resolve Rafiqu’s housing situation, food provision, and new work permit application.” There you go – an admission that all through February, the housing situation had to be repeatedly attended to, among other things. Exactly as we described.

The second point that MOM made was that “Rafiqu was transferred to a dormitory in Tuas by his employer, but needed to make a 2-and-a-half-hour commute to pick up his meals at Gambas Avenue. TWC2 alleged that MOM was unable to take further action in response to Rafiqu’s concerns about the travelling time and costs to collect his meals.

“This is not true. Following MOM’s intervention, Rafiqu’s employer was agreeable to provide him with transport allowance to pick up his meals. The MOM officer also advised Rafiqu to have his meals at Gambas Ave while continuing to search for a new employer.”

But that’s what we said in the story. We wrote: “MOM reassured him that the company would arrange for all his meals, but added that the meals were to be picked up at the company office at Gambas Avenue. Rafiqu would also be paid an allowance for public transport.

“In theory, well and good. In practice, it would be absurd. Gambas Avenue, Rafiqu estimated, was two and a half hours’ roundtrip by public transport from the dorm in Tuas.”

As readers can see, we noted the transport allowance in our story, but also pointed out that it was absurd for Rafiqu to commute like this for each meal. Interestingly, MOM’s “rebuttal” confirms that it was a two-and-a-half hour commute. Does the ministry expect praise for its handling of the matter just because there is a theoretical solution to Rafiqu’s meals, however absurd and impractical a solution that is?

More seriously, despite MOM accusing us of “inaccuracies and misinformation”, everything that MOM has said in its statement only confirms what we reported in our story. By making such a baseless accusation, is the ministry itself not engaging in misinformation?