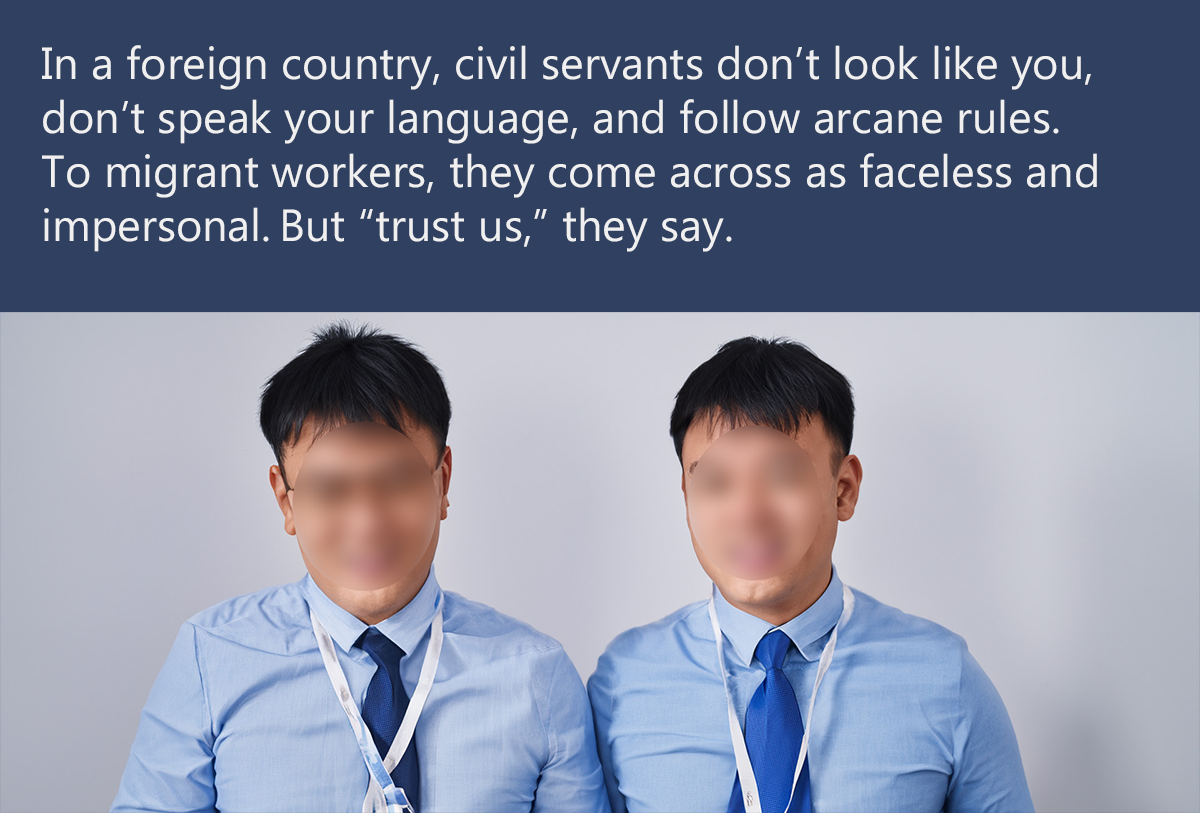

How civil servants look to migrant workers (AI-generated image)

Robiul (name changed) emerges from the sidewalk with what can only be described as a home-made cast on his left foot. He has ingeniously fashioned a boot from what appears to be layers of gauze over a hard cast, secured to a slipper using a collection of rubber bands. With the support of a single crutch, he approaches the TWC2 volunteers seated around a table in front of a restaurant. Seeing his condition, the table collectively shifts to make room, and someone brings a chair so he can sit down.

It turns out that Robiul fell from a ladder on 13 June 2024 during a renovation job and fractured his left foot. The injury will put him out of action for at least six to eight weeks. He has a medical report from the hospital, all in English, and is seeking help in navigating the next steps.

Singapore’s Work Injury Compensation Act (Wica) provides a process to protect a worker’s right to medical treatment, medical leave wages and, should there remain any permanent impairment despite treatment, lump-sum compensation. The rules require employers to notify the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) no later than ten days after the employer came to know of the accident.

We make a quick check and discover that the accident has not been reported. The employer surely knows about the injury since Robiul has been on medical leave, as ordered by his doctor, and his foot is visibly in a cast. It is concerning that no report has been made.

Workers themselves can report accidents to MOM and we naturally advise Robiul to do so. A volunteer starts to jot down some pointers on a piece of paper, as cues for him when he goes to make the report.

Robiul’s body language starts to shift. He pauses, stares off in the distance, not speaking for several moments. He turns to a friend who came with him and starts a side conversation. The friend translates some of what Robiul is saying but not all of it. However the TWC2 volunteers hear enough of it to sense that Robiul is hesitant to do as advised and is more concerned about his employment status during this time than his recovery.

But isn’t it a cut and dry situation? “You have to report the accident to MOM to protect yourself and stay in Singapore for treatment, Robiul,” we say.

And we wonder: why is reporting to MOM seen as something to be feared?

After some back and forth, the friend finally translates Robiul’s misgivings, explaining: He doesn’t want to be seen as going against his boss or aggravating the situation. At the core, he fears losing his job in Singapore and being sent back if he gets on his employer’s bad side.

We can understand how crucially important a job is to a migrant worker from Bangladesh. An entire family depends on his income. So he is operating on the assumption that if he helps his boss keep the accident away from MOM’s eyes, he will be able to keep his job and get all necessary medical treatment. Be nice to the boss and the boss will look after all your needs.

The volunteers get a little frustrated with this line of thought. We have seen too many cases where a worker tries to be nice to the boss, but the boss does not see it in his interest to be nice to the worker. Ultimately, the boss is a businessman, and from his point of view, it boils down to costs – of medical treatment, of a long period of recovery (medical leave wages), accommodation, and the absence of one worker from the work crew for a prolonged period.

Many of these costs are covered by the Wica insurance that the employer will have bought, but if no Wica report is made, the insurer will likely refuse to pay. Then these costs will have to be shouldered by the employer himself. In such an instance, it will quickly become apparent to the boss that it will be incomparably cheaper to just cancel the worker’s Permit and send him home.

So, contrary to Robiul’s instincts, being nice to the boss may result in losing both his job and his right to healthcare. And yet it’s a struggle trying to convince him of that. But why are his instincts the way they are?

Socialised differently

The good thing about Singapore is that – most of the time, at least – our systems work. They produce the intended results. It is safe to say that most Singaporeans have an innate understanding that going through the proper channels and following protocol can usually be trusted to yield a fair or the desired outcome. If there’s a law or process, however bureaucratic and impersonal, adherence to it gets us where we need to go. We see that for example in the complex systems and maze of documentation that low-income households have to navigate in order to justify their need for financial aid even if we can debate about whether the quantum is sufficient. But in the end they do get aid.

In short, Singaporeans have trust in systems.

This is not true of all countries. In some places, systems do not deliver. Corruption or abuse of power and privilege can severely skew outcomes.

Corruption has been described as a scourge in Bangladesh, which ranked 149th on the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index. Its low score of 29 indicates ‘serious corruption problems’ in the public sector, according to Transparency International. (Singapore ranked 5th with a score of 83.) Official channels can be trusted to offer no guarantees or protections. Lower-income households also disproportionately bear the burden of bribery. Transparency International Bangladesh’s 2021 household survey, which looked at corruption in service sectors, found that the burden of bribery was seven times higher on lower-income households than higher-income ones, in terms of monthly income. As they are less capable of paying bribes, their access to services (and fair outcomes) is more limited.

The realities Bangladeshis are accustomed to are radically different from Singaporeans’. Their realities are a reliance on bribes, under-the-table exchanges and connections. If one is from a stratum of society without access to money or power, one is likely to be ignored by whatever systems that may theoretically exist. As a result, there is pervasive distrust of official avenues and remedies.

Individuals like Robiul will have long learnt that to compensate for their disadvantages they need to maintain personal connections with people who are more powerful or better resourced than they are. They learn to pay attention to vertical relationships that can offer protection.

The boss is seen as one such protector. Between relying on the goodwill of a boss or trusting a bureaucratic process to protect one’s interests, it’s a no-brainer. Of course, the personal relationship matters much more, and more likely to deliver.

Exploiters

Sadly, this cultural difference is not only evident to the volunteers at TWC2. If the steady flow of workers coming to TWC2 saying they have been cheated is anything to go by, there is no lack of Singaporean employers actively exploiting this difference in culture. We frequently have workers telling us that prior to their coming to their jobs in Singapore, they were told that their salary would be, say, $650 a month. But their paper documentation, emblazoned with MOM letterhead, might show, say, $520 a month as their salary. They ask their agents or future employers why the difference. The answer is often along the lines of “don’t worry about it, it’s only for [tax/quota/bureaucratic] reasons”.

And workers believe these replies. The “explanation” chimes with their deep-seated distrust of official systems and with what they have learned – governmental systems are to be manipulated to get around illogical obstacles. Between the solemn word given at a personal level (“Don’t worry, you will get the agreed salary”) and a documented discrepancy, too many workers place faith in the solemn word.

Then after the worker with a lower salary stated in his papers arrives in Singapore, works a month and sees his first paycheck, he is shocked to discover that it is the lower of the two salary levels. If the worker protests, the boss simply points to the documented (lower) salary, knowing full well that, except in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that will be the enforceable salary. The boss will have successfully duped the worker by exploiting the latter’s cultural bias.

One month later

Our caseworkers monitor Robiul’s case and one month later, we see that the employer has still not notified MOM about the accident. One month is too long. Section 35(3) of the Work Injury Compensation Act says:

Every employer must, within the prescribed time after the employer first has notice of an accident giving rise to work injury to any employee of the employer, give notice of the accident to (a) the Commissioner in the form and manner specified by the Commissioner; and (b) the employer’s insurer in writing.

Section 3(1) of the subsidiary Regulations specifies that the prescribed time for an employer to give notice of an accident to the Commissioner and the employer’s insurer under section 35(3) of the Act is ten days.

It is an offence to fail to notify MOM, and the penalty set out in Section 35(8) is a fine not exceeding $5,000; for repeat offenders, a fine not exceeding $10,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or both.

We have reason now to suspect that Robiul’s trust in the goodwill of his employer is misplaced. Without an official filing, Robiul can be sent home at any time even if medical treatment is not completed. Should there be any permanent impairment to his foot, he is not entitled to compensation. We ask him to come down to see us. We need to try again to persuade him that reporting the accident to MOM is in his best interest.

Update after this article was drafted: The case has finally been notifed to the ministry.

15261