Caption for photo

This is the fourth of a series of articles commenting on the results of the Ministry of Manpower’s (MOM’s) Migrant Worker Experience and Employer Survey 2024. The results were released in the third week of August 2025. In this Part 4, we will focus on the In-principle Approval letter and salaries.

IPAs

The Ministry of Manpower’s In-Principle Approval (IPA) is a very important document for migrant workers. Besides its primary function of informing prospective foreign employees that they have work passes ready for them, the document also contains key details about their salary, allowances and deductions.

These salary-related details should be identical to whatever terms of employment they had agreed to in their negotiations with their employers. While the courts have ruled that the IPA document is not itself a contract (it being a document between MOM and employers), its details are supposed to be aligned with the terms of employment contract, whether written or verbal, that employer and employee had entered into.

Unless a court is satisfied that what had been agreed had genuinely been different from what’s stated in the IPA, a court will enforce the terms stated on the IPA as if those were the terms within the contract. Of course, this exposes the employer to the accusation that what they had declared to MOM to obtain the IPA was a false declaration.

Who is the ‘migrant worker’?

MOM’s survey report speaks of the ‘migrant worker’. The survey’s scope was limited to Work Permit holders in non-domestic sectors. In other words, domestic workers are not part of this discussion.

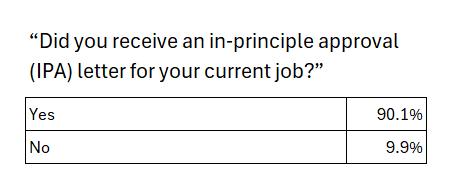

It was therefore troubling to see from MOM’s own survey that in 2024, only 90.1% of respondents said they received an IPA for their current job. About one in ten did not.

It is the law that employers must pass a copy of the IPA to the migrant worker, and yet here we have data that perhaps one in ten employers blatantly flouted the law. This is no innocent matter because, as TWC2 has seen through our casework, employers have been known to agree with the worker that his salary should be, say, $600 a month, but quietly declare to MOM that the agreed salary was $450. The lower figure is then incorporated into the IPA, but if the employer fails to provide a copy of the IPA to the worker, the worker will have no idea that the employer had falsely declared a lower salary.

When the migrant worker is later not paid what he was expecting, he may find it an uphill task to prove to a court that the mutually agreed salary was $600. Too often, the terms of employment had been verbal and there is little evidence to show that a different salary had been agreed to.

The 90% compliance rate from MOM’s own survey is a seriously low figure. It should be 100%, especially when it is the law.

Salaries

The next question in the survey was whether participants received the salaries stated in their IPAs. As a stand-alone question it had little value, and we will explain why below. First, look at the answers.

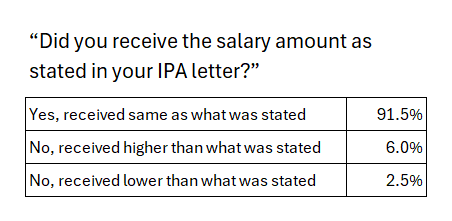

MOM reported that 91.5% of participants said they received the same salary that the figure stated on their IPAs.

6.0% said their salary was higher than the IPA figure, whilst 2.5% said it was lower.

These numbers raise many other questions, yet this was a stand-alone question. Without follow-up questions, it is difficult to draw any clear meaning from the data obtained.

Readers might instinctively focus on the 2.5% who were being paid less than what was stated in their IPAs. Indeed, this datapoint is cause for concern, but the figure that really jumped at us was the 6.0% who received more than what their IPAs said. It raises a lot of questions.

How so?

The normal expectation is that the IPA salary applies for the first year of work, possibly the first two years of work (if it is a two-year Work Permit). Just like Singaporeans, it is reasonable to expect inflation adjustments and salary increments annually. Yet, we also know that many migrant workers work an average of four years with the same employer (TWC2’s own survey). Logically therefore, at any given time, about three-quarters of them would have worked longer than a year, and yet only 6.0% are paid more than their starting salary?

Does this not suggest wage stagnation despite inflation?

And wage stagnation has wider consequences. It means that workers cannot realistically advance their careers and earning power by being loyal to their employers. They need to change jobs as frequently as they can manage, in order to get ahead. This kind of employee churn cannot be good for skills and experience retention in firms, and must surely have an impact on overall productivity levels in our economy.

That’s the reading from this datapoint, at least at its face value.

To have real value, MOM’s survey question should have come with several related questions, such as how long they have been with the same employer. The published data should also explain whether workers who have had their Work Permits renewed also received new IPAs and, if so, did these new IPAs represent salary rises above the previous IPAs.

Only then can we grasp the true significance of the 6.0% figure.

The survey also had a question about the mode of salary payment. 92% of participants said they received their salaries through their bank accounts. This is broadly in line with what TWC2 has observed. It is a notable improvement from years past.