Arriving in our mailbox earlier this week was a new booklet published by the Ministry of Manpower, titled ‘6 Simple Steps to comply with Employment Laws’. This is indeed a good initiative; from here on, employers will have fewer excuses not to do things in accordance with the law.

The six ‘simple steps’ featured in the booklet are:

1. Issue written key employment terms to workers within 14 days from start of employment;

2. Keep a record of your workers’ attendance and working hours;

3. Pay your workers their salary and overtime payment correctly and on time;

4. Issue itemised pay slips to your workers;

5. Make prompt & accurate contributions to your workers’ CPF account (this does not apply to work permit holders);

6. Make sure your workers are given their leave entitlements.

There are issues which TWC2 can foresee which unfortunately the booklet does not address. There are also examples at the back of the booklet which mislead.

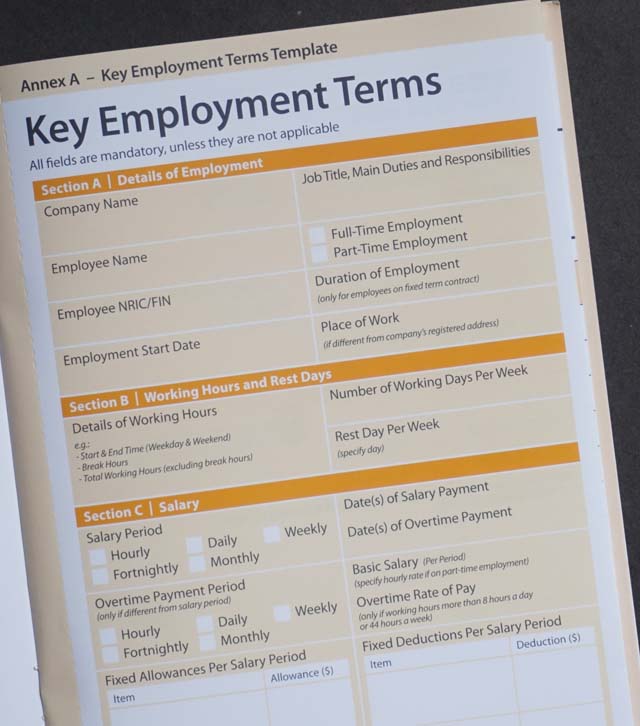

Key Employment Terms

With respect to the section on Key Employment Terms (KET), it says that the list should be issued to employees by the 14th day from start of employment. But what if the terms there are different from the terms as stated in the In-Principle Approval for Work Permit, or in a contract signed earlier? This is going to be a source of much dispute.

If the KET — which does not require the employee’s prior written consent — contains elements that are adverse to a foreign worker and yet are issued after he has paid heavy recruitment costs and led to believe (through the IPA terms) that there would be better terms, how can the KET be valid in law? First of all, it would potentially violate Section 6A of Part IV of the Fourth Schedule of the Employment of Foreign Manpower (Work Passes) Regulations, which says that a foreign worker’s basic monthly salary cannot be reduced, or his deductions increased from whatever was declared in the work pass application (in effect, the IPA) without his prior written consent.

Secondly, it would be a case of contract substitution, which internationally is recognised as falling within the prohibitions of the Palermo Protocol on Trafficking in Persons. Singapore has acceded to this Protocol and has domesticised its provisions through our Prevention of Human Trafficking Act 2014. Contract substitution has the characteristics of fraud and deception, abuse of power, and abuse of the position of vulnerability of the victim, clearly outlined in Sections 3(1) (c), (d) and (e) of this Act.

A 2009 speech by Roger Plant. Head, Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour at the International Labour Office, mapped out how the ILO, of which Singapore is a member, saw this issue:

Yet most forms of exploitation on today’s labour markets, which can involve some degree of coercion, are very subtle…. A common practice is “contract substitution”, where they sign one contract in their home country, but are later compelled to sign a totally different one in the place of destination.

— Trafficking for Labour Exploitation – Conceptual Issues, and Challenges for Law Enforcement, by Roger Plant, Kiev, April 2009Presentation to Fifth International Law Enforcement Conference, Kiev, 31 March- 2 April 2009

Our KET does not even require the employee to sign and agree to the terms. It would be most egregious if we consider KETs, unilaterally issued by employers after the worker has started on the job, to be binding.

As a better solution, TWC2 has long proposed a Standard Employment Contract (SEC), which should be signed prior to taking up the job, and which — the signed version, that is — should be submitted alongside the application for a work permit. Naturally, the details declared in the application should be aligned with the SEC. An SEC has the benefit of being a document that is agreed to by both parties in advance and would have the weight of case law in terms of contract enforcement. By contrast, KET merely throws a new spanner into the works.

![]()

Language

The booklet is bilingual. The templates and examples at the back of the booklet are provided in English and Chinese versions. Nowhere in the booklet however, does it say that KETs, payslips or other documents provided by employer to employee must be in a language that the worker can understand.

TWC2 has seen cases where Bangladeshi workers are given time cards and payslips in Chinese. They cannot figure out what the numbers in them are supposed to represent. And then they are blamed for not raising inaccuracies or miscalculations earlier.

This is just not right. The very act of an employer in issuing documents in an incomprehensible language to employees must be treated as prima facie cause for suspicion.

In other areas of life, we have seen a gradual move to do away with legalese when vendors issue “terms and conditions” accompanying a contract or sale, be it for insurance policies, buying a tractor or joining a gym. The moral impulse is the same: to be fair and transparent to the less empowered and less specialised party.

By the same token, there should also have been a clear statement by MOM that all documents to employees must be in a language that they can understand. The templates should have been in

English+Chinese,

English+Tamil,

English+Bengali,

English+Burmese,

English+Pilipino

English+Punjabi

English+Hindi… and so on.

![]()

Shocking examples

Right at the back of the booklet, MOM has a few examples of how these forms should be filled up. Look at this one. It is more than a bit puzzling. The term “Regular hours” has a commonplace meaning of working hours for which the basic salary should apply. This is to be distinguished from “Overtime hours”. Yet, the numbers in blue filled in for “Regular hours” actually reflect total hours.

Either the header should say “total hours” or the numbers in the example are plain misleading.

Moreover, look at the entry for “09/05/15”, which was a Saturday. It shows four regular hours (when the man worked from 9am to 7pm) but no overtime hours! Did anyone proof-read the booklet before publication?

Next, look at this example of a pay slip, below. There is a deduction of $200, completely unexplained. Does MOM condone this? When the whole point of the booklet is to improve transparency in the employment relationship, how can employers be misled to think that they can insert unexplained deductions?

Even worse, near the bottom right corner, the formula is wrong! The net pay should be A + B – C + D + E. The only way it can be A + B + C + D + E (as shown in the published booklet) is if the deduction amounts (that is, C) are shown as negative numbers, which they are not.

Lastly, look at the “Mode of payment”. The example says “Cash”. Paying workers in cash permits all manner of shenanigans. TWC2 has long recommended that it be mandatory for employers to pay workers through bank systems. Doing so creates an independently maintained audit trail that makes it easier to verify whether salaries have actually been paid. Other major destination countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Qatar have already implemented this rule. Why is MOM dragging its feet?

TWC2 hopes a revised edition of this booklet is promptly issued.